The always entertaining Jacob Kaplan-Moss recently posted a missive,

"Snakes on the

Web", which, if you haven't already read it, is a highly edifying trip

through a variety of Python web technologies and history. He begins

with a simple statement — "Web development sucks." — and goes on to

ask a number of interesting questions about that.

What sucks about web development? How will we fix it? How has python fixed it, and how will python fix it in the future? While I can't say I agree with every answer, I found myself nodding quite a bit, and he has something useful to say on just about every point.

I noticed one very important question he leaves out of the mix, though, which seems more fundamental than the others: why does web development suck? In particular, why do so many people who are familiar with multiple styles of development feel like developing for the web is particularly painful by comparison, while so much of software development moves to the web? And, why does web development in Python suck, despite the fact that otherwise, Python mostly rocks?

Programming for the web lacks an important component, one that Fred Brooks identified as crucial for all software as early as 1975: conceptual integrity. Put more simply, it is difficult to make sense of "web" programs. They're difficult to read, difficult to write and difficult to modify, because none of the pieces fits together in a way which can be understood using a simple conceptual model.

Rather than approach this head on, from the perspective of a working web programmer, let's start earlier than that. Let's say someone approached you with a simple programming task: write an accounting system that includes point-of-sale software to run a small business. Now, considering some imagined requirements for such a system, how many languages would you recommend that it be written in?

Most working programmers would usually say "one" without a second thought. A too-clever-by-half language nerd might instead answer "two, a general-purpose programming language for most things and a domain specific language to describe accounting rules and promotions for the business". Why this number? Simply put, there's no reason to use more, and introducing additional languages means mastering additional skills and becoming familiar with additional quirks, all of which add to initial development time and maintenance overhead. Modern programming languages are powerful enough to perform lots of different types of tasks, and are portable across both different computer architectures and different operating systems, so other concerns rarely intrude.

But, in the practical, working programmer's world, what's the web's answer to this question? Six. You have to learn six languages to work on the web:

Of course, Jacob lists a pile of related technologies too, and rightly points out that it's a lot to keep in your head. But he is talking about a problem of needing extensive technical knowledge, something which all programmers working in a particular technology ecosystem learn sooner or later. I'm talking about a different, more fundamental problem: in addition to the surface problem of being complex and often broken, these technologies are fundamentally conceptually incompatible, which leads to a whole host of other problems. Furthermore, the only component which is really complete is the "middle-tier" language, although bespoke web-only languages like PHP and Arc manage to screw that up too.

Here are a few simple example problems that are made depressingly complex by the impedence mismatch between two of these components, but which are incredibly easy using a different paradigm.

How do you place two boxes with text in them side-by-side? Using a GUI toolkit, like my favorite PyGTK, it often goes something like this:

Plus, how do you discover how these layouts work? There are a variety of reference materials, but no canonical guide that says "this is exactly what a <table> tag should do, and how it should look". There are different forms of documentation for both.

If you have a variable number of elements, you quickly run into another problem. Should this be the responsibility of the HTML, the CSS, or some code (in the templating layer) that emits some HTML or some CSS? Should the code in the templating layer be written as an invocation of your middle-tier language, or should the template language itself have some code in it? Reasonable people of good conscience disagee with each other in every possible way over every one of these details.

This is all part of a very complex problem though. For all of these crazy hoops you have to jump through, HTML and CSS do provide a layout model that allows you to do some very pretty and very flexible things with layout, especially if you have large amounts of text. Perhaps not as good as even the most basic pre-press layout engine, but still better than the built-in stuff that most GUI toolkits allow you. So there is an argument that this complexity is a trade-off, where you get functionality in exchange for the confusion. So let's look at a much simpler problem.

Let's say that, in our hypothetical accounting application, you have a list of items in a retail transaction, and you want to process the list and produce a sum. Where is the right place to do that? It turns out you have to write the code to do that three times.

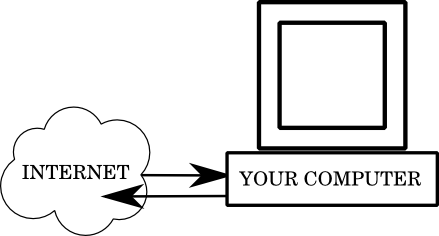

First, you have to write it in JavaScript. After all, the numbers are all already in the client / browser, and you want to update the page instantaneously, not wait for some potentially heavily-loaded server to get back to you each time the user presses a keystroke. And why not? You've got plenty of processing power available on the client.

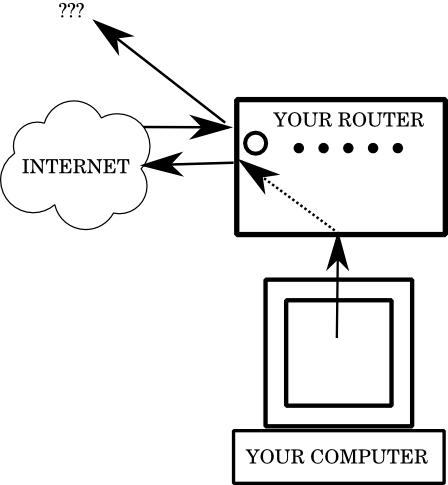

Then you have to write it in Python. That's where the real brain of the application lives, after all, and if you're going to do something like send a job to a receipt printer or email a customer or sales representative some information in response to a sale, the number has to be located in the middle tier.

Finally you have to do it in SQL. Since this is a traditional web application, your Python code is going to be spread out among multiple servers, and the database is the ultimate arbiter of recorded truth. So you need to have transactions around the appropriate points and execute any interesting aggregate functions (such as SUM()) in the database tier.

So, you've got three times as much work to do in your fancy new web application as you would in a simple record-based application with a GUI. A worthy price to pay to run in the brave new world of tomorrow rather than on some crusty old client/server system, right?

Well, as it turns out, the problem is somewhat deeper than that. It turns out that JavaScript, Python, and SQL actually have slightly different numerical models (in fact Python implements at least 4 itself: fixed-point decimal, floating-point decimal, IEEE 754 floating-point binary, and integer math; you should really only use decimal for money, but this isn't availble in JavaScript and its availability in SQL is spotty). After applying some discounts, your register might read $19.74 but your receipt will read $19.75; and the reports sent to the accounting department will read $19.74898989898989.

Even if you know a lot about math on computers, the limitations of each of these runtimes, and you happen to get all of that just right, you still have another problem to contend with: what happens when somebody else needs to change the logic in question? How do you test that the Python, the JavaScript, and the SQL are all still in sync? It's possible, but you have to go above and beyond the usual discipline of test-driven development, because you need to have integration tests that verify that different, almost unrelated code, in different languages, in different environments is all executing properly in lock-step. Just getting the code from SQL and JavaScript to run in your Python test suite at all is a major challenge; in a language like PHP it's borderline impossible.

This is all even worse when it comes to security, because every part of the application exposes an attack surface, and because you can't use the same language or the same libraries to do any of the work, they all expose a different attack surface.

In his talk, Jacob notes that "frameworks suck at inter-op", but the problem is much deeper than that. As I've shown here, a single page from a single application written using a single framework, which has only one task to do, can't even inter-operate with itself cleanly, at least not at the level that Jacob wants — or that I want. He says, "gateways aren't APIs", and he's right: the correct way to inter-operate is through well-defined APIs. APIs can be discovered through a single, consistent process. Their implementations can be debugged using a single set of development tools.

CSS isn't an API. HTML isn't an API. Strings containing a hodgepodge of SQL and data aren't an API either.

It's not all doom and gloom, but my ideas for a future solution to this problem will have to wait for another post.

What sucks about web development? How will we fix it? How has python fixed it, and how will python fix it in the future? While I can't say I agree with every answer, I found myself nodding quite a bit, and he has something useful to say on just about every point.

I noticed one very important question he leaves out of the mix, though, which seems more fundamental than the others: why does web development suck? In particular, why do so many people who are familiar with multiple styles of development feel like developing for the web is particularly painful by comparison, while so much of software development moves to the web? And, why does web development in Python suck, despite the fact that otherwise, Python mostly rocks?

Programming for the web lacks an important component, one that Fred Brooks identified as crucial for all software as early as 1975: conceptual integrity. Put more simply, it is difficult to make sense of "web" programs. They're difficult to read, difficult to write and difficult to modify, because none of the pieces fits together in a way which can be understood using a simple conceptual model.

Rather than approach this head on, from the perspective of a working web programmer, let's start earlier than that. Let's say someone approached you with a simple programming task: write an accounting system that includes point-of-sale software to run a small business. Now, considering some imagined requirements for such a system, how many languages would you recommend that it be written in?

Most working programmers would usually say "one" without a second thought. A too-clever-by-half language nerd might instead answer "two, a general-purpose programming language for most things and a domain specific language to describe accounting rules and promotions for the business". Why this number? Simply put, there's no reason to use more, and introducing additional languages means mastering additional skills and becoming familiar with additional quirks, all of which add to initial development time and maintenance overhead. Modern programming languages are powerful enough to perform lots of different types of tasks, and are portable across both different computer architectures and different operating systems, so other concerns rarely intrude.

But, in the practical, working programmer's world, what's the web's answer to this question? Six. You have to learn six languages to work on the web:

- HTML. This isn't really a programming language, but in web

development you do end up reading and writing quite a lot of

it.

- CSS. In order to apply visual styles to your HTML so that it

actually looks nice in a browser, you need to understand a different

language (with a different conceptual model for how documents are laid

out than the HTML itself).

- JavaScript. In today's competitive AJAX-y world, you need to

be able to react instantly in the browser, writing a real client

application.

- SQL, so that you can store your data in a database.

- Your "middle-tier" language: in my case and Jacob's, that would be

Python. This is where people tend to spend the bulk of their

programming time, but not all of it.

- A templating language; in Jacob's case, the Django template language.

Of course, Jacob lists a pile of related technologies too, and rightly points out that it's a lot to keep in your head. But he is talking about a problem of needing extensive technical knowledge, something which all programmers working in a particular technology ecosystem learn sooner or later. I'm talking about a different, more fundamental problem: in addition to the surface problem of being complex and often broken, these technologies are fundamentally conceptually incompatible, which leads to a whole host of other problems. Furthermore, the only component which is really complete is the "middle-tier" language, although bespoke web-only languages like PHP and Arc manage to screw that up too.

Here are a few simple example problems that are made depressingly complex by the impedence mismatch between two of these components, but which are incredibly easy using a different paradigm.

How do you place two boxes with text in them side-by-side? Using a GUI toolkit, like my favorite PyGTK, it often goes something like this:

left = Label("some text")The conceptual model here is simple: the HBox() is a container, the "left" and "right" things are widgets, which are in that container. You can add them, remove them, swap them, or handle events on them easily. You can discover how these things are done by reading the API references for the appropriate classes of object. However, there's no right answer to this question on the web. You can use a <table> tag, and then some <tr>s and <td>s to make a single-row table with two cells, but that has a variety of limitations; plus, it's considered somehow gauche by most web designers to use tables for layout these days. Or, you could cook up a collection of CSS classes. So there's the first impedence mismatch: do you do layout in HTML, or CSS? Of course most design gurus would like to tell you that "always and only CSS" is the right answer here, but more practically-minded web developers who actually write code will often prefer HTML, partially because it's simpler but partially because CSS's featureset is incomplete and there are some things you can still only do with HTML, or only do portably with HTML.

right = Label("some other text")

box = HBox()

box.add(left)

box.add(right)

Plus, how do you discover how these layouts work? There are a variety of reference materials, but no canonical guide that says "this is exactly what a <table> tag should do, and how it should look". There are different forms of documentation for both.

If you have a variable number of elements, you quickly run into another problem. Should this be the responsibility of the HTML, the CSS, or some code (in the templating layer) that emits some HTML or some CSS? Should the code in the templating layer be written as an invocation of your middle-tier language, or should the template language itself have some code in it? Reasonable people of good conscience disagee with each other in every possible way over every one of these details.

This is all part of a very complex problem though. For all of these crazy hoops you have to jump through, HTML and CSS do provide a layout model that allows you to do some very pretty and very flexible things with layout, especially if you have large amounts of text. Perhaps not as good as even the most basic pre-press layout engine, but still better than the built-in stuff that most GUI toolkits allow you. So there is an argument that this complexity is a trade-off, where you get functionality in exchange for the confusion. So let's look at a much simpler problem.

Let's say that, in our hypothetical accounting application, you have a list of items in a retail transaction, and you want to process the list and produce a sum. Where is the right place to do that? It turns out you have to write the code to do that three times.

First, you have to write it in JavaScript. After all, the numbers are all already in the client / browser, and you want to update the page instantaneously, not wait for some potentially heavily-loaded server to get back to you each time the user presses a keystroke. And why not? You've got plenty of processing power available on the client.

Then you have to write it in Python. That's where the real brain of the application lives, after all, and if you're going to do something like send a job to a receipt printer or email a customer or sales representative some information in response to a sale, the number has to be located in the middle tier.

Finally you have to do it in SQL. Since this is a traditional web application, your Python code is going to be spread out among multiple servers, and the database is the ultimate arbiter of recorded truth. So you need to have transactions around the appropriate points and execute any interesting aggregate functions (such as SUM()) in the database tier.

So, you've got three times as much work to do in your fancy new web application as you would in a simple record-based application with a GUI. A worthy price to pay to run in the brave new world of tomorrow rather than on some crusty old client/server system, right?

Well, as it turns out, the problem is somewhat deeper than that. It turns out that JavaScript, Python, and SQL actually have slightly different numerical models (in fact Python implements at least 4 itself: fixed-point decimal, floating-point decimal, IEEE 754 floating-point binary, and integer math; you should really only use decimal for money, but this isn't availble in JavaScript and its availability in SQL is spotty). After applying some discounts, your register might read $19.74 but your receipt will read $19.75; and the reports sent to the accounting department will read $19.74898989898989.

Even if you know a lot about math on computers, the limitations of each of these runtimes, and you happen to get all of that just right, you still have another problem to contend with: what happens when somebody else needs to change the logic in question? How do you test that the Python, the JavaScript, and the SQL are all still in sync? It's possible, but you have to go above and beyond the usual discipline of test-driven development, because you need to have integration tests that verify that different, almost unrelated code, in different languages, in different environments is all executing properly in lock-step. Just getting the code from SQL and JavaScript to run in your Python test suite at all is a major challenge; in a language like PHP it's borderline impossible.

This is all even worse when it comes to security, because every part of the application exposes an attack surface, and because you can't use the same language or the same libraries to do any of the work, they all expose a different attack surface.

In his talk, Jacob notes that "frameworks suck at inter-op", but the problem is much deeper than that. As I've shown here, a single page from a single application written using a single framework, which has only one task to do, can't even inter-operate with itself cleanly, at least not at the level that Jacob wants — or that I want. He says, "gateways aren't APIs", and he's right: the correct way to inter-operate is through well-defined APIs. APIs can be discovered through a single, consistent process. Their implementations can be debugged using a single set of development tools.

CSS isn't an API. HTML isn't an API. Strings containing a hodgepodge of SQL and data aren't an API either.

It's not all doom and gloom, but my ideas for a future solution to this problem will have to wait for another post.