Over thanksgiving weekend, the always excellent Ying purchased a very thoughtful gift for me - the Logitech diNovo Edge⢠keyboard.

They keyboard itself is very slick. If you want to read a thorough review of

the various features, I suggest here

or here; but

the best thing about this keyboard from my point of view is that Logitech

has produced a grown-up looking product here without unnecessary features.

It's simple, graceful, beautiful, and works well. This is really what the

diNovo line should have originally been. I was very excited about, and

ultimately very disappointed by, the original diNovo offering, so I can't

help but compare it.

The previous diNovo looked cool, but it was a miniature circus. It was a

keyboard, a bluetooth hub, a mouse, a charger, a detachable keypad, a

calculator, an LCD display, custom software, and a partridge in a pear tree.

The mouse charger / bluetooth hub combo itself had 4 wires coming out of the

back: a PS2 mouse plug, a PS2 keyboard plug, a USB plug, and power. The

software was intended to be used as a "media hub", aggregating all kinds of

bluetooth devices into a whirlwind of frustration and insanity. (Bluetooth

support still isn't great on most computers, but back then, it was

positively obscene.)

The Edge is almost the exact opposite. There are 3 things in the box: a tiny

USB receiver dongle, the charging stand, and the keyboard itself. Whereas

the previous diNovo was thin and sleek, the Edge is incredibly

pretty. It is actually made out of glass that was cut with a

laser. The keyboard's two unusual features, an integrated trackpad

(sorry, "TouchDisc") and volume slider, are tastefully small and relegated

to the right side of the keyboard. Rather than hedge its bets with a

detachable number pad, the new Edge makes a bolder statement: this isn't a

keyboard for excel jockeys doing data-entry, and if it is, they're classy

enough excel jockeys that they can touch-type on the number row.

The keyboard's bluetooth implementation is flawless. I've associated it with

3 different Bluetooth hubs already, and none of them took more than a second

to work with it. It provides all of its buttons and features over standard

protocols rather than requiring, as the original "Media Desktop" diNovo did,

special drivers and custom hub hardware to take full advantage of it.

Despite this superior implementation, it has no pretensions to being a

"media desktop" - it's a wireless keyboard. This is most clearly evidenced

by the dongle: although the keyboard uses Bluetooth to communicate, the

supplied dongle does not expose any Bluetooth functionality or require any

Bluetooth drivers on your PC: it looks like a regular USB keyboard. If

you've never been through the hell of configuring a bluetooth device, the

significance of this merciful act may be lost on you, but trust me: it is

the difference between suffering through 10 hours of obscure configuration

error messages, and just plugging in a functioning keyboard.

And that brings me to the main event. Others have reviewed this keyboard's

various features and suitability under Windows or the Mac; I'm going to tell

you about Linux. I did suffer through those configuration error

messages, but for good reason.

Out of the box, the keyboard almost works with Linux. All the

special keys, the volume control, and the packaged dongle worked instantly,

and that was pretty surprising. Even forgetting about driver issues,

bluetooth devices typically take a few moments to "warm up".

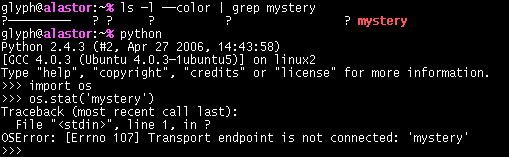

There is a problem, however. Although the TouchDisc produces events of some

kind, and is recognized as a mouse by Linux, the /dev/mouseX device produces

no output. Similarly, nothing happens on /dev/input/mice. Telling Xorg to

look at the devices created by the TouchDisc -- for example, to treat the

output from the /dev/eventX as an evdev or /dev/tsX as synaptics device --

results in a segfault or an infinite hang, respectively.

I suspect that within a year or two, the Linux drivers will be fixed, but

until then there is another option: configure the device with a different

bluetooth hub. This post

over at UnixAdminTalk pointed me in the right direction, and I

originally tried using it with my

original Bluetooth adapter. In this configuration, all of the

keyboard's features worked: the optional keys, the TouchDisc, scrolling,

etc. The problem is that I'd have to set up a potentially fragile

boot-script to run the appropriate commands, and I'd be unable to use the

keyboard to navigate my boot menus. Since I need to use Windows quite often

on this computer, that was not really an option for me.

So there's a third option, which is what I'm sticking with.

The ANYCOM USB bluetooth Adapter "USB-250" was on sale at my local

electronics store. It was hard to find an adapter that explicitly mentioned

this feature, but it has a HID gateway (what they refer to as "mouse and

keyboard binding") - the same feature that allows the Logitech dongle to

start instantly at boot rather than waiting for OS drivers to tell it to

pair. To do this, I had to install the most recent drivers from ANYCOM's

website, run a program to flash the dongle, and then pair with the

keyboard.

Once that's done, unfortunately, the dongle doesn't work properly as a

Bluetooth (i.e. HCI) device in Linux. It just looks like a USB keyboard and

mouse. The bluetooth feature shows up, but I wasn't able to get any of the

Bluez utilities to tell it to talk to other devices, and hid2hci thinks it's

already in HCI mode. Also, the keyboard's "special" buttons (and the volume

slider) don't work through the ANYCOM's USB emulation in Linux! The

important thing, though, is that it enables the keyboard at boot, and

provides a functioning USB mouse emulator which allows it to be used in both

operating systems. In Windows, the drivers transition it properly back into

Bluetooth mode and I can use other Bluetooth devices. Again, I'm hopeful

that the Linux driver situation will improve with time.

To sum up, you can get two of the following three features in linux right

now: availability at boot, the touchdisc, and a the volume slider and FN

key.

Personally, that's good enough for me, both because the keyboard is

beautiful and because I'm using it in a unique situation. My desktop PC is

also my media center PC. I want a keyboard that works for both.

While occasionally inconvenient, this dual-purpose hardware setup is

intentional. My PC needs to switch to TV mode in order to watch TV, so the

lovely donor of this keyboard can't turn on loud and colorful TV shows

within my ADD-riddled line of sight while I'm trying to work at home.

Similarly, I can't get distracted and wander off to work while we're

watching a movie together.

I have gone through several other, cheaper, wireless keyboards, all of them

too shoddy to even bother reviewing[1]. I have long wanted one which was

good enough to be taken seriously as a desktop keyboard (as good as or

better than the Déck) but simultaneously wireless, so I can pick it up and

drag it to the couch when necessary. The Edge provides all that, plus the

bonus of having a tiny footprint. Space is at a premium on my very, very

small desk, and I now have enough room with the keyboard put away to use the

same space to fill out forms and read books.

[1]: Hint: if you are going to buy a non-Bluetooth wireless product from

Logitech, make sure that the "wireless" icon on the box also says

"Pro", or you are going to get something with a range of 3 feet and a

tendency to drop data entirely. There's no other indication of this massive

difference in quality. My experience of other brands is even worse than that

of Logitech's low-end offering.

Of course, all of this is moot unless the keys feel good. After working with

several aggressively clickety keyboards for the last few months, it's a

stark contrast. The keys are extremely quiet by normal standards, and

completely silent when compared to an EnduraPro.

It's difficult to describe the precise feel of the keys. I'm not sure what

the phrase they use to describe it, the (ahem) "PerfectStroke⢠Key System"

is supposed to mean. It feels like a sturdier version of the first diNovo's

keys. One test I perform on scissor keyboards is pushing down one corner of

the key to see how evenly the key as a whole will depress. Cheaper switches

wiggle quite a bit, and the original diNovo had this problem so badly that

the "alt" key eventually just gave up entirely.

The keys have very little travel, and a medium-to-well-defined click at the

point of their activation, followed by a sort of "cushioned" feel when

you've pressed past that point. They're normal sized. The keyboard's layout

thankfully doesn't have any surprises (beyond the usual Logitech

reconfiguration attempting to make the "Insert" key harder to hit, which I

entirely approve of). I haven't quite gotten back up to the typespeed scores

I could achieve with the Déck, but I've improved quite a bit after only a

day. I don't expect there will be much of a difference.

While it's hard to say without a lot of hard use, I am hopeful that the keys

are of a generally higher quality than the previous iteration. Although I

had to use the older one for almost a year to break the "alt" key, many of

the mildly disconcerting features of its keys aren't present here.

Describing these phenomena would be tedious and difficult without diagrams,

but they definitely aren't there. Most of all, the first iteration simply

had the phrase "scissor keys" to describe the switches, but this version has

a paragraph of prose devoted to its "key system". That could certainly just

be sophistry, but it is encouraging to know that the product development

people are devoting more attention to the key part of the keyboard.

Logitech also states that they're using 10-million-cycle switches now, which

while it doesn't live up to the insane specifications of the EnduraPro (25M

cycles) or the Déck (50M cycles) still isn't the default "we don't

say how many cycles our keys can handle", which is generally 1M or less.

The trackpad's not fantastic. It's a little hard to hit the right mouse

button. The duplicate left mouse button on the left side of the keyboard is

a nice touch though, allowing you to easily use the mouse while standing and

holding the keyboard with both hands on either side. The trackpad is also

sluggish, which is a bit of a pain because I have the very high-resolution

G7 mouse plugged in as well, and there's no speed which accommodates them

both. It wouldn't be usable for gaming. Still, it is quite a lot nicer than

other integrated trackpads I've used, and its small size makes it ideal for

the occasional need to tap a control or two while watching a movie or

playing a game on the TV.

The Edge is a very nice keyboard. If you have a dual-purpose computer

situation like mine, you may find it ideal. Indeed, it is the only keyboard

I've yet seen that can handle both the "media center" and "desktop wireless

keyboard" jobs equally well. It can even be made to work with Linux,

although depending on what you want it can be a little bit of a pain. If you

know your way around a command line and are willing to buy another bit of

hardware it you can almost certainly get it set up the way you like it,

though.

No review of a diNovo product can really conclude without mentioning the

price. It's a $200 keyboard. I know, it's ridiculous. I am thrilled that

Ying decided to spring for it, because despite heavy interest, I was pretty

sure I wouldn't get it for myself after being disappointed by the original

diNovo boondoggle.

However, this stylish and apparently high-quality keyboard is now serving

two purposes: providing the quality key switches of a $100+ wired desktop

keyboard, and one which would have been filled by a $90-or-so wireless

keyboard. I have also been disappointed by and returned several

just-sub-$100 wireless keyboards which don't have the range or small size

required to sit comfortably on the couch. So, while Logitech could certainly

lower the price without their customers complaining, at some level it makes

sense. It's expensive, but especially for the keyboard aficionado with a

wired home and a lot of typing to do, it isn't necessarily a waste of

money.