I suffer from ADHD.

Photo by Taylor Young on Unsplash

Photo by Taylor Young on Unsplash

Update 2021-08-22: Almost exactly a year after this post was written, I sought

and received a clinical neuropsychiatric diagnosis of

ADHD (predominantly

inattentive,

sluggish cognitive

tempo), so I’m no

longer self-diagnosed.

I want to be clear: when I say I suffer from this disorder, I am making a

self-diagnosis. I’ve obliquely referred to suffering from ADHD in previous

posts, but rarely at any length. The main reason for my avoidance of the topic

is that it still makes me super uncomfortable to write publicly about a

“self-diagnosis”, since there’s a tremendous amount of Internet quackery thanks

to amateur diagnosticians.

This despite the fact that I’ve known for the past 15 years that I have ADHD.

I am absolutely not trying to set myself up as a maverick unlicensed

freelance

psychiatrist here. If you think you might have ADHD, or any other ailment,

whether mental or physical, call your primary care physician. Don’t email me.

At the same time, for me, this diagnosis is not really ambiguous or in a gray

area. This is me looking down and noticing I’ve only got one arm, and

diagnosing myself as a one-armed person. I’ve taken numerous ADHD screening

questionnaires and reliably scored well into the range of “there is no

ambiguity whatsoever, you absolutely have ADHD”, so I feel confident to

describe myself as having it.

Terminology aside, this post is about a set of cognitive and metacognitive

issues that I have, and some tools that I found useful to remedy them. I think

others might find those same tools useful in similar situations. So if you’re

also uncomfortable with the inherently unreliable nature of self-diagnosis, or

the clinical specificity of the term “ADHD” — and I absolutely don’t blame

you if you are — I invite you to read “ADHD” as a shorthand for some character

traits that I informally believe fit that label, and not a robust clinical

analysis of myself or anyone else.

With that extended disclaimer out of the way, I’ll get started on the post

itself; and where better to do that than at the start of my own challenges.

The ‘Laziness’ model

Photo by Zosia Korcz on Unsplash

Photo by Zosia Korcz on Unsplash

Throughout my childhood, I was labeled an “underachiever”. I performed well on

tests and didn’t do homework. I was frequently told by adults — especially my

teachers — that I was “brilliant” but

“lazy”.

Was I lazy? Is there even such a thing as “laziness”? Here’s a spoiler for

you — “no” — but I didn’t know that at the time. All I knew was that I

couldn’t seem to do certain things — boring things: homework, long division,

and cleaning up my room, for a few examples. I couldn’t seem to do the things

that my peers found routine and trivial.

This is a common enough experience that it shows up clearly even in systematic

reviews and meta-analyses of adult sufferers of

ADHD. Everybody

tells you you’re lazy, and so you believe it. It sure looks like laziness from

the outside!

In retrospect, that’s the interesting problem with this false diagnosis: “from

the outside”. Assuming for the moment that laziness does in fact exist and is

a salient character flaw, what would the experience of the interiority of

such laziness actually feel like?

It seems unlikely that it would feel like I what I actually felt at the time:

-

Frequently, suddenly remembering, in contexts where it wouldn’t help —

walking to school, in an unrelated class, while walking to work — that I had

to Do The Thing.

-

Anxiously, yearningly, often desperately wishing I could Do The Thing.

-

Trying to Do The Thing at the responsible time, finding that my mind would

wander and I would lose several hours of time... sitting for hours,

literally bored to tears, while I attempted and failed to Do The Thing.

-

At long last, finally managing to start. Once I was truly exhausted and

starting to panic, I’d drink a gallon of heavily-caffeinated and very sugary

soda at 2 in the morning and finally finally find that I suddenly had

the ability to Do The Thing, and white-knuckle my way through an all-nighter

to finish The Thing. (This step was more common after I got to my late

teens; before that, The Thing just wouldn’t get Done.)

Sitting up night after night destroying my mental and physical health,

depriving myself of sleep, focusing with every ounce of my will on tasks that I

absolutely hated doing but was forcing myself to complete at all costs: it

doesn’t seem to line up with the popular conception of what “laziness” might be

like! Yet, I absolutely believed that I was lazy. If I were not lazy,

surely Doing The Thing wouldn’t be so difficult!

I took pains at the start of this post to point out that mental health

diagnosis is usually best left to professionals. I think that at this point in

the story I should emphasize that “I’m lazy” is also itself a self-diagnosis,

and — at least in every case where I’ve ever heard it used — a much worse one

than “I have ADHD”.

If you are not a licensed psychologist or psychiatrist, any time you decide

with certainty that someone (even yourself!) has an intrinsic, persistent

character flaw, you’re effectively diagnosing them. If you decide that they’re

inherently lazy, or selfish, or arrogant, you’re effectively diagnosing them

with a sort of personality disorder of your own invention.

So, although I didn’t see it at the time, laziness didn’t seem to describe me

terribly well. What description fits better?

The ‘Attention Deficit’ model

Photo by Tom Bradley on Unsplash

Photo by Tom Bradley on Unsplash

In my late 20s, my Uncle Joel gave me a gift that changed my life: the book

“Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and Coping with Attention Deficit

Disorder” by Edward M. Hallowell. The

life-changing aspect of this book was not so much that it showed that there

were other people “like me”, or that my problem had a name, but that it gave me

a different, and more accurately predictive,

model to understand my

own behavior.

In other words, it allowed me to see — for the first time — that the scarcest

resource limiting my efficacy wasn’t the will to do the work, but rather the

ability to focus. With this enhanced understanding, I could select a more

effective strategy for dealing with the problem.

I did select such a strategy! It worked very well — albeit with some caveats.

I’ll get to those in a moment.

Although my limiting factor was the ability to pay attention, the problem that

prevented me from recognizing this was one of

metacognition — the way I was

thinking about how I think.

My early model of my own mind was that I was a lazy person who just needed to

do what I had assumed everyone else must be doing: forcing myself to do the

tasks that I was having trouble completing. If I really wanted to get them

done, then what possible other reason could there be for me to not do them?

The ‘laziness’ model didn’t generate particularly good predictions. For any

given project at school, it would predict that I would not try very hard to do

it, since the very dictionary definition of ‘lazy’ is “unwilling to work or

use energy”. The observed behavior, by contrast, was constant, panicked,

intense (albeit failed, or at least highly inefficient) uses of significant

amounts of energy.

The main reason to have a model of a thing is to make predictions about that

thing. If the predictions that a model gives you are consistently wrong,

then the model isn’t directly useful. At that point, it’s time to discard it

and find a better one. At the very least, it’s time to revise the model in

question until it starts giving you more accurate, actionable information.

The ‘laziness’ model is wrong, but worse than that, it’s harmful. What it

routinely predicts, regardless of context, is that I need more negative

self-talk, more ‘motivation’ in the form of vicious self-criticism, more

forcing myself to “just do it”. All of these things, particularly when

performed habitually, cause real, significant

harm.

If I gave myself the most negative self-talk I could muster, the most vicious

criticism, and really put Maximum Effort into forcing myself to do the thing I

wanted done... if it didn’t work, of course that just meant that I needed to

engage in even more self-abuse! I could always try harder!

This is the worst way that a model can be inaccurate: an unfalsifiable,

self-reinforcing prediction. I could never demonstrate to myself that I’d

really been as unkind to myself as was possible; there was always room for

escalation. Psychologically, it’s also the worst kind of behavioral advice,

which is the kind that generates a self-reinforcing negative feedback loop.

Once I started putting my newfound knowledge into practice, the difference

between interventions predicated on an understanding of the problem as “lack of

usable attention span” and those based on “lack of willpower” was night and

day. I stopped trying to white-knuckle my way through all of my challenges

and developed non-judgmental ways to remind myself to do things.

I knew that I, personally, was never going to spontaneously remember to do

things at the right time, so I developed ways of letting computers remind me.

I knew that I’d never be able to stick with routine, repetitive tasks, so I

made a unified list of all the tedious administrative tasks I need to perform.

I can’t keep important dates and times in mind, so I rely completely upon my

calendar.

Even given these successes, “it worked!” is a colossal oversimplification.

Today, it’s about 15 years later, and I’m still sifting through the

psychological rubble wrought by the destructive, maladaptive coping mechanisms

that I just described, and still trying to find better ways to remain effective

when I’m feeling distracted... which is most of the time.

Simply having a better model at the coarsest level is just the first step.

Instantiating that model in a working, fleshed out technological system is a

ton of work in its own right. But it’s work that starts having little

successes, which is a lot easier to build on and maintain momentum with than

the same failure repeated day after day.

Given that I was starting — nearly from scratch — at 25, and had a lifetime

worth of bad habits to unlearn, constructing a workable system that addressed

my personal organizational needs still took the better part of a decade.

So as I move into the next, slightly more prescriptive section here, I don’t

want to give anybody the idea that I think this is easy.

Don’t give up!

Listen up, Simon. Don’t believe in yourself. Believe in me! Believe in the

Kamina who believes in you!

Kamina, Episode 1,

Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann

At the start of this post, I specifically mentioned that I hadn’t wanted to

write at length about ADHD due to my discomfort with self-diagnosis. So, you

might be wondering: what was it that overcame this resistance and prompted me

to finally write about my own experiences with ADHD?

The original inspiration was a pattern of complaints about suffering from ADHD

I see periodically — mainly on Twitter — that look roughly like this:

- “ADHD means never being on time for a meeting and having no excuse, forever.”

- “It’s great to have ADHD and never be able to complete a routine task. Sigh.”

- “I can’t take out the trash and my roommates just can’t understand that this

is just part of who I am and I will never get better.”

- “Why can’t neurotypicals understand that I’m just never going to “get stuff

done” like they can. It’s exhausting.”

These are paraphrased and anonymized on purpose; I really don’t want to direct

any negative attention towards someone specific, particularly someone just

venting about struggles.

Of course, no blog post in mid-2020 would be complete without some reference to

the ... situation. The original inspiration for this post predates the dawn

of the new hell-world we all now inhabit, but, to say the least, COVID-19

has presented some new challenges to the coping mechanisms I’m writing about

here. (Still, I know that I’m considerably better off than the average

American in this mess.)

The message I’m trying to get across here is hopeful — others suffering with

executive-function deficits similar to mine might be able to do what I did and

fix a lot of their problems with this one weird trick! — and the constant

drumbeat of despair all around us right now makes that sort of message feel

more urgent.

Posts like the ones I described above seem to represent a recurring pattern of

despair, and they make me sad. Not because I can’t identify with them; I have

absolutely had these feelings. Not even because they’re wrong, exactly: it

really is harder for folks with ADHD to handle some of these situations, and

the struggle really is lifelong.

They make me sad because they’re expressing a fatalistic perspective; a fixed

mindset that precludes any hope of future improvement. The through line

that I have seen from all of these posts is a familiar, specific kind of

despair; a thought I’ve had myself multiple times:

When somebody that I care about asks me, ‘Can you do the dishes later?’, I

want to say ‘yes’ and have them believe me. I want to be able to believe

myself, and I don’t think I will ever be able to.

Unlike myself when I was younger, the authors of these posts already have a

name for their problem: ADHD. Sometimes they’ve even tried some amount of

therapy or even medication.

Even so, they’re still buying in to the maladaptive strategy of “just try

harder”. Since they already know that ADHD is, at least in part, a structural

brain difference, they despair of ever being able to actually do that though,

which leaves “giving up” as the only viable strategy.

Don’t give up! I believe in you!

I have had another lifelong problem since when I was young: I am severely

nearsighted. Yet, I never developed any psychological hangups around that;

nobody ever told me that I needed to buckle down and just squint harder.

This problem was socially quite well understood, so… I got glasses. Then I

could see, as long as I consistently used those glasses.

Nobody ever expected me to be able to see without glasses.

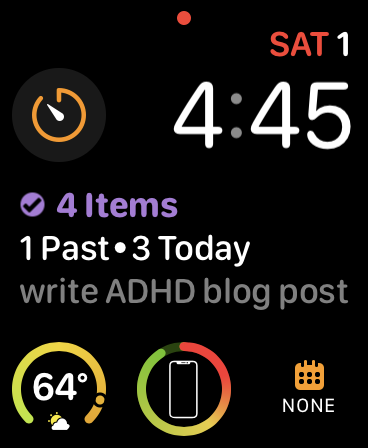

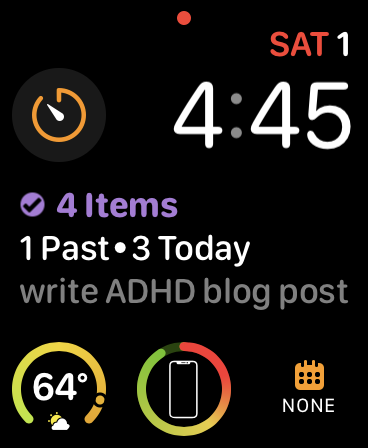

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash

Calendars, to-do lists, and systems like Getting Things

Done are the corrective

lenses for the ADHD brain..

If a to-do list is a corrective lens for ADHD, one of the major issues around

understanding how to use it is that the mass-market literature around to-do

lists assumes a certain level of neurotypicality. Assistive devices may

frequently be useful to non-disabled

people, but their

relationship to and use of such affordances is very different.

Through the Looking-Glass ...

Let’s stretch this lens metaphor into absurdity.

In our metaphorical world, ADHD is myopia, and so most — or at least many —

folks are “sight-typical”. Productivity systems are our “lenses”.

If nearsightedness were as poorly understood as ADHD, and you were nearsighted,

you wouldn’t be able to pop on down to Lenscrafters and pick up a pair of

spectacles. You might realize that the problem was with your eyes, and think,

“lenses might help me see farther”. Many kinds of lenses might be commercially

available in such a world! Lenses for telescopes, cameras, microscopes...

The way that someone with 20/20 vision might use a lens to see farther is to

use a telescope to see something really far away. But you, my

hypothetically-nearsighted friend, don’t need a powerful zoom lens to take

surveillance photographs from a helicopter. Even if you could make such lenses

work to correct your vision, you wouldn’t want to carry a pair of 2-kilogram

DSLR zoom lenses everywhere you go. You want eyeglasses, which are something

different.

Photo by James Bold on Unsplash

Photo by James Bold on Unsplash

The lenses in eyeglasses are — while operating on fundamentally the same

principles of optics as the lenses in a telescope or a microscope — constructed

and packaged in a completely different way. But most importantly, the way you

use them is to wear them every day, not to deploy them on special occasions in

the rare event where you need to do something extreme, but all the time, every

day, in the same way.

... and What I Found There

Photo by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

Photo by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

A person with nominal executive function might use the occasional free-floating

to-do list to track a big, complex project with a lot of small interrelated

tasks. Most folks in the modern information-driven economy routinely need to

do projects that are too complex to easily memorize all the required steps.

Even doing your own personal taxes has enough steps to require at least a

little bit of tracking.

Such a person could make a to-do list for that one project — their telescope,

if you will — put it in a place where they’d remember to look at it when

they’re working on that project, and then remember to check things off when

they’re done.

They could have one to-do list on the fridge for groceries, a note on their

phone for stuff to get for their spouse, and a wiki page outlining some tasks

at work. They would probably have enough free-floating executive

function to remember which

list maps to which project and when each project is relevant, and remember to

check each one at the appropriate time.

I spent a lot of time trying to make disconnected to-do lists like this work

for me. They never have. Even when I’m feeling particularly productive there

is a cycle of list-generation, that goes like this:

-

When I want to work on the project in question, I can’t remember where the

to-do list is, but I need to figure out what I need to do again.

-

So I go and write a new to-do list, spend a bunch of time rewriting the one

I’d already written but can’t quickly find. Then I do some work on the

project, check off a few things, and put the list away.

-

Later, I’ll find both lists, both half checked off, and now I waste a bunch

of time trying to figure out which one is the right one.

-

Repeat this process a few times, and now I have a dozen lists. The lists

themselves start generating more work than the actual project, because now I

am constantly re-making and finding lists, trying to figure out which one is

the most up to date.

This is the simplest case, but the real problem happens at a higher level:

one of the biggest problems caused by any executive function deficit like ADHD

is the difficulty of task initiation.

The more irrelevant distractions I can see while I’m trying to work out what to

do next, the harder that decision becomes. And there’s nothing quite so

distracting as the detritus of a thousand half-finished to-do lists.

One List To Rule Them All

What I’ve found works for me is a single, primary to-do list that I can

obsessively check in with every minute of every day, which subsumes every other

list related to every other project in my life.

I’m hardly the only person to have this insight — if you start engaging with

the “productivity” noosphere, reading all the books, listening to the podcasts,

this is a recurring theme. You don’t just have an ‘app’ or a ‘list’, you have

to have a System. It has to be reliable; you have to know you’re going to

keep checking it, or it’s worthless for storing your commitments. But

unfortunately this is frequently buried under a lot of other technical

complexity about the fiddly details of how to set up one system or the other.

It’s very easy to miss the forest for the trees.

Having ADHD means that I routinely forget what I’ve decided to do over the

course of only a minute or two after I’ve decided to do it. Just this week, I

had to remind myself no fewer than three times to write down “buy more olive

oil” because I kept remembering that we were running low when I was in the

kitchen and by the time I finished washing my hands to put it into my phone I’d

already forgotten why I did that and went back to making dinner.

I need to write everything down. I’m not going to remember five or six, or

even two or three places to check for what to do next. I need to have one

place to check what comes next, and then build the habit of constantly going

back to it, both to add new things and to see what needs to be done.

Technology can help. Technology might even be necessary — it is for me.

But if you’re considering trying this out for the first time, be mindful that

piles of to-do apps can be just as distracting as piles of paper. The

important thing is to clearly, singularly decide on the one place which is

the ‘root’ of your task tracking system.

You can even do this with a pen and paper. Carry the same, single notebook

with you everywhere, and make it absolutely clear that it is your primary

list, which is where you have to put any references to other lists. Some

people have a lot more success with something tactile, to engage all the

senses.

For me personally, the high-tech portion of this strategy is indispensable. I

use a combination of OmniFocus for

things that have to be done and Apple’s built-in calendar application for

places I have to be at a particular time.

OmniFocus defines the core gameplay

loop

of my life. Rather than having to cultivate and retain an elaborate series of

interlocking habits and rituals to remain functional, I have a single root

habit which triggers every other habit.

That habit? Consulting the unified “what should I do next” perspective in

OmniFocus. Every time I am even marginally distracted, I check that view

again.

Any time I have trouble initiating a task, I start breaking down the top task

in that list into smaller and smaller “next physical

action”.

I don’t even rely on myself to do this; since I know I’ll forget to break

things down, I frequently make tasks that look like this:

- thing I want to do

- plan the thing I want to do

- break down the planning task into tiny actions and write them down here

- break down the task itself into tiny actions and write them down here

To reduce distraction, I routinely close down any windows that are not

necessary for whatever I’m currently working on. Particularly, I routinely

sweep to get rid of browser

tabs, asking (as I would with an

email) “does this window represent a task I should do?”. If yes, it goes in

the task system, if no, I close it so it won’t distract me further.

To facilitate this clean-up, on every computer that I use, I have a global

hot-key set up to turn the thing that I’m looking at — some selected text, an

image, an email message, a browser tab, a chat message at work — into a task

that I can look at later.

Everything I have to do on a regular basis is in this system as a recurring

task; for example:

- taking out the trash

- doing the dishes

- logging in to Jira at work to look for assigned tasks

- checking my email

- brushing my teeth

Yes, even basic personal hygiene is in here. Not because I’ll necessarily

forget, or that it takes a lot of energy, but I don’t want to waste one iota

of brainpower I could be devoting to my current task to worrying about

whether I might need to do something else later. If I don’t see ‘brush teeth’

in my “what should I do next” view, then I know, with certainty, that I don’t

need to be thinking about tooth-brushing right now.

The “what should I do next” view is available on all of my computers, on my

tablet, on my phone, and it even dominates my watch-face; I check it more often

than I check the time:

No single feature is a hard requirement of my system; I could get along

without any one of them in a pinch. However, the way that they combine to

constantly reinforce what the next thing I need to do is in any given context,

at any given time, means that I need to expend less energy trying to

consciously hang on to all the context.

Limitations and Risks

I don’t want to give an overly rosy view of this strategy. Getting a single

unified to-do system that works for you is not the same as getting a brain

that can remember to do stuff. So here are some caveats:

- Implementing and maintaining such a system is never easy. It just takes

tasks like ‘making sure I renew my passport before I need to travel’, ‘show

up on time for the meeting’ and ‘buy a gift at least a week before the

wedding’ from totally impossible to possible to do at least somewhat

reliably with a sustainable level of effort. The main thing that I believe

is possible for everyone is being able to commit to simple future tasks.

- Building enough data about one’s own habits and procrastination triggers

also takes time, and to make such a system effective, one needs to do that

work as well. (A passive time-tracking tool like Screen

Time on your phone or

RescueTime on your workstation can be quite

illuminating — and surprising.)

- The initial wave of relief I felt when I started tracking tasks masked a

gradual increase in my general anxiety over time. Checking and re-checking

the ‘what to do next’ list can become a bit of an anxious compulsion, a

safety behavior

that doesn’t always help me plan my day. As one builds the habit of

routinely checking the list, it’s important to avoid developing constant

anxiety about the list as the only motivation to do so.

- Similarly, it is important to learn to under-commit. Not only does one

need to avoid putting an unrealistic amount of stuff into the system,

everybody (but especially everybody with ADHD!) needs non-trivial chunks

of unstructured, unplanned time, where the system will clearly say ‘nothing

to do now, just relax’. The “poor

self-observation”

and “time blindness” symptoms of

ADHD ensure that properly estimating things before committing is a constant

challenge that never really goes away either.

- This strategy definitely won’t be sufficient for some folks. ADHD is a

spectrum and there’s no precise mechanism to calibrate where you are on it.

Some folks will respond really well to this strategy, some folks will need

medication before it helps to a useful degree.

Finishing up (about finishing up)

If you’re suffering from ADHD and despairing that you will never finish a task

or be on time to an appointment: you can. It’s possible to do it at least

pretty reliably. I believe if you commit to one and only one task

tracking system, and consistently use it every single day, all the time,

you can commit to tasks and get them done.

If you do it consistently enough, it will eventually become muscle memory, and

not something you need to consciously remember to do every day.

It’s still never going to be easy to Do The Thing, even if your digital brain

can perfectly remember what The Thing is right now.

At the very least, it was possible for me to learn to trust myself when I say

that I will do something in the future, by designing a system around my own

limited attention, and if I can do it, I think you can too.

Acknowledgments

This was a big one! I’d like to particularly thank my Uncle Joel, without whom

this post (and many of my other achievements) would not be possible for the

reasons described above, as well as Moshe Zadka, Amber

Brown, Tom Most, and

Eevee for extensive feedback on previous drafts of this

post.

Additionally, I’d like to thank David Reid for introducing

me to many of the tools and techniques that I still use every day, and Cory

Benfield, Jonathan Lange, and Hynek

Schlawack for many illuminating conversations over the years

about the specifics and detailed mechanics of the tools whose use I describe in

this post.

Any errors, of course, remain my own.