I like making computers do stuff. I find that getting a computer to do what I

want it to produces a tremendously

empowering feeling. I think

Python is a great language to use to tell computers

what to do.

In my experience, the most empowering feeling (albeit often, admittedly, not

the most useful or practical one) is making one’s own computer do something

cool. But due to various historical accidents, the practical bent of the

Python community mainly means that we get “server-side” or “cloud” computers to

do things: in other words, “other people’s computers”.

If you, like me, are a metric standard tech industry hipster, “your own

computer” means “macOS”. Many of us have written little command-line tools to

automate things, and thank goodness macOS is enough of a UNIX that that works

nicely - and it’s often good enough. But sometimes, you just want to press a

button and have a thing happen; sometimes a character grid isn’t an expressive

enough output device. Sometimes you want to be able to take that same logical

core, or some useful open source code, that

you would use in the cloud, and instead, put it into an app. Sometimes you

want to be able to learn about writing desktop apps while leveraging your

existing portfolio of skills. I have done some of this, and intend to do more

of it at

work,

and so I’d like to share with you some things I’ve learned about how to do it.

Back when I was a Linux user, this was a fairly simple proposition. All the

world was GTK+ back then, in the blissful interlude between the ancient

inconsistent mess when everything was Xt or Motif or Tk or Swing or XForms, and

the modern inconsistent mess where everything is Qt or WxWidgets or Swing or

some WebKit container with its own pile of gross stylesheet fruit salad.

If you had a little script that you wanted to put a GUI on back then, the

process for getting started was apt-get install python-gtk and then just to

do something like

| import gtk

w = gtk.Window("My Window")

b = gtk.Button("My Button")

w.add(b)

gtk.main()

|

and you were pretty much off to the races. If you wanted to, you could load a

UI file that you made with glade, if you had some

complicated fancy stuff to display, but that was optional and reasonably

straightforward to use. I used to do that all the time, for various personal

computing tasks. Of course, if I did that today, I’m sure

they’d all laugh at me.

So today I’d like to show you how to do the same sort of thing with macOS.

To be clear, this is not a tutorial in Objective C, or a deep dive into Mac

application programming. I’m going to make some assumptions about your skills:

you’re a relatively experienced Python programmer, you’ve done some

introductory Xcode material like the

Temperature Converter

tutorial, and you either already know or don’t mind figuring out

the PyObjC bridged method naming conventions

on your own.

If you are starting from scratch, and you don’t have any code yet, and you want

to work in Objective C or Swift, the modern macOS development experience is even

smoother than what I just described. You don’t need to install any “packages”,

just Xcode, and you have a running app before you’ve written a single line of

code, because it will give you a working-by-default template.

The problem is, if you’re a Python developer just trying to make a little

utility for your own use, once you’ve got this lovely Objective C or Swift

application ready for you to populate with interesting stuff, it’s a really

confusing challenge to get your Python code in there. You can drag the

Python.framework from homebrew into Xcode and then start trying to call some

C functions like PyRun_SimpleString to get your program bootstrapped, but

then you start running into tons of weird build issues. How do you copy your

scripts to the app bundle? How do you invoke distutils? What about shared

libraries that you’ve linked against? It’s hard enough to try to jam anything

like setuptools or pip into the Xcode build system that you might as well give

up and rewrite the logic; it’ll be less effort.

If you’re a Python developer you probably expect tools like

virtualenv and

pip to “just work”. You expect to be able

to put a file into a folder and then import it without necessarily writing a

whole build toolchain first. And if you haven’t worked with it a lot, you

probably find Xcode’s UI bewildering. Not to mention the fact that you

probably already have a text editor that you like already, and don’t want to

spend a bunch of time coming up to speed on a new one just to display a button.

Luckily, of course, there’s pyobjc,

which lets you write your whole application in Python, skipping the whole Xcode

/ Objective C / Swift side-show and just add a little UI logic. The problem

I’m trying to address here is that “just adding a little UI logic” (rather than

designing your program from the ground up as an App) in the Cocoa / ObjC

universe is

famously and maddeningly obscure.

gtk.Window() is a reasonably straightforward first function to call;

[[NSWindow alloc] initWithContentRect:styleMask:backing:defer:] not so much.

This is not even to mention the fact that all the documentation, all the

tutorials, and all the community resources pretty much expect you to be working

with .xibs or storyboards inside the Interface Builder portion of Xcode, and

you’re really on your own if you are trying to do everything outside of that.

py2app can help with some of the build

issues, but it has

its own problems you

probably don’t want to be

tackling if you’re just getting

started; it’ll sap all your energy for actually coding.

I should mention before we finally dive in here that if you really just want

to display a button, a text area, maybe a few fields,

Toga is probably a better option for you than

the route that I'm describing in this post; it's certainly a lot less work.

What I am assuming here is that you want to be able to present a button at

first, but gradually go on to mess around with arbitrary other macOS native APIs

to experiment with the things you can do with a desktop that you can't do in

the cloud, like displaying local

notifications,

tracking your

location,

recording the

screen,

controlling other applications,

and so on.

So, what is an enterprising developer - who is still lazy enough for my

rhetorical purposes here - to do? Surprisingly enough, I have a suggestion!

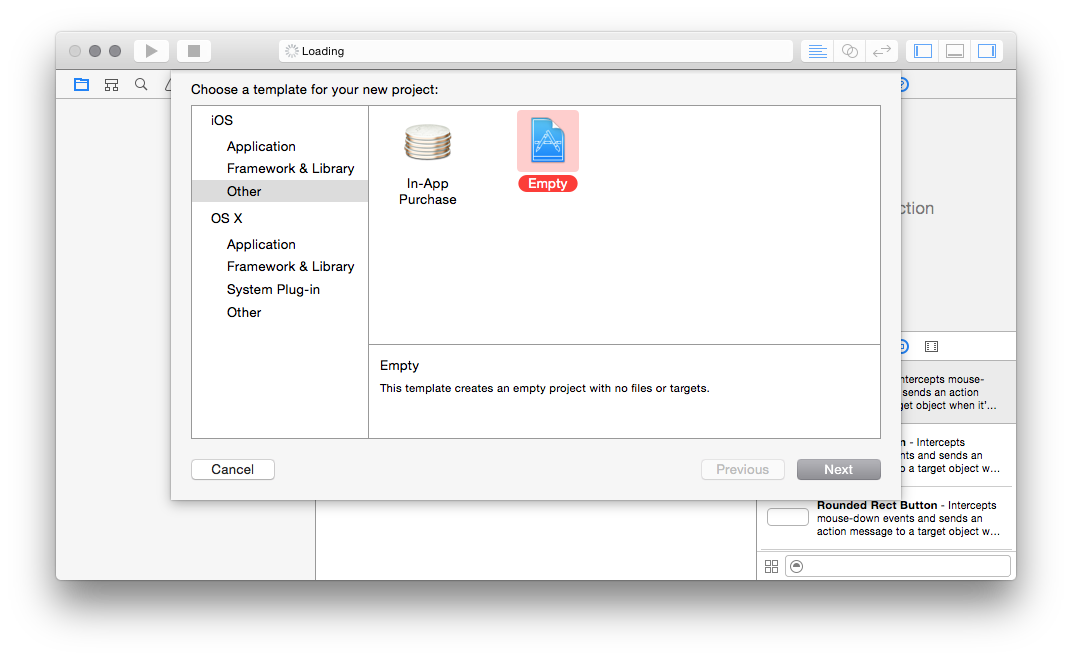

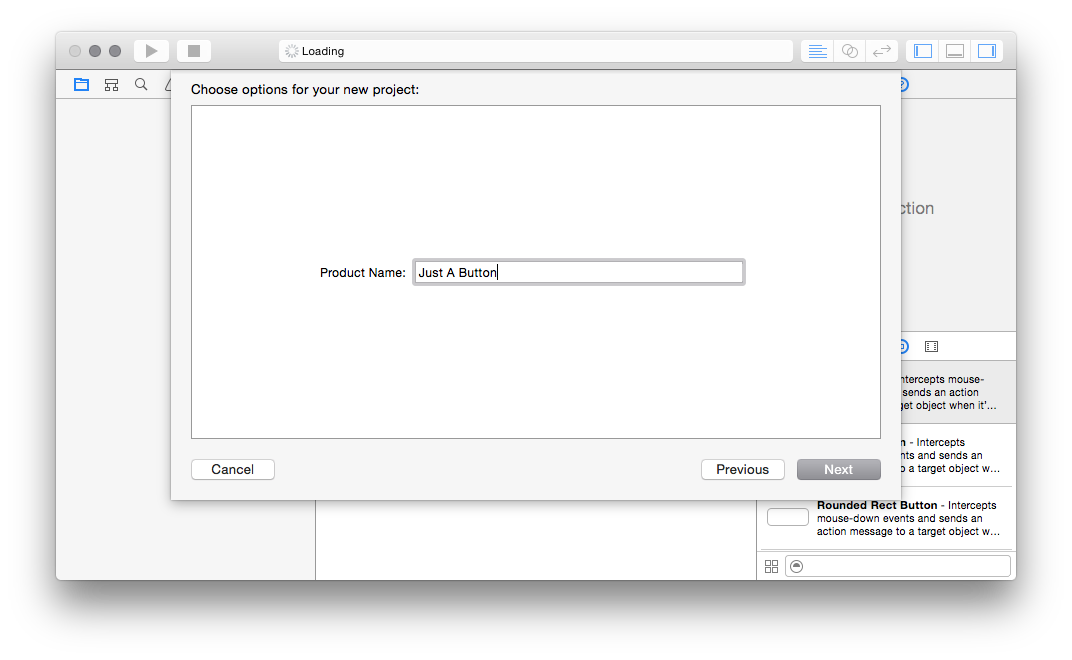

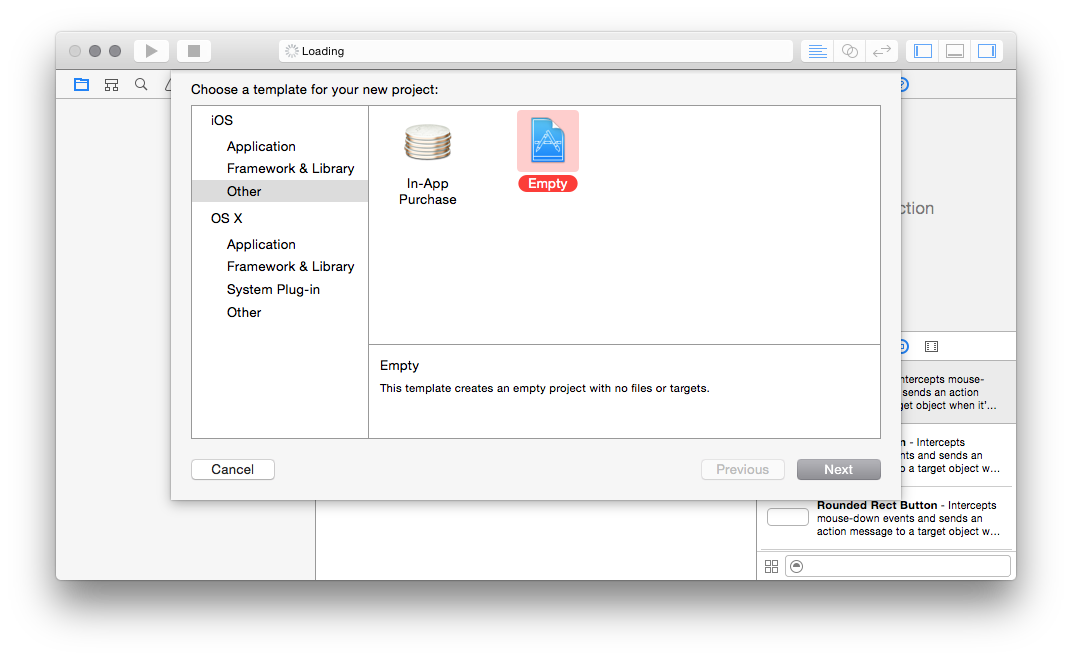

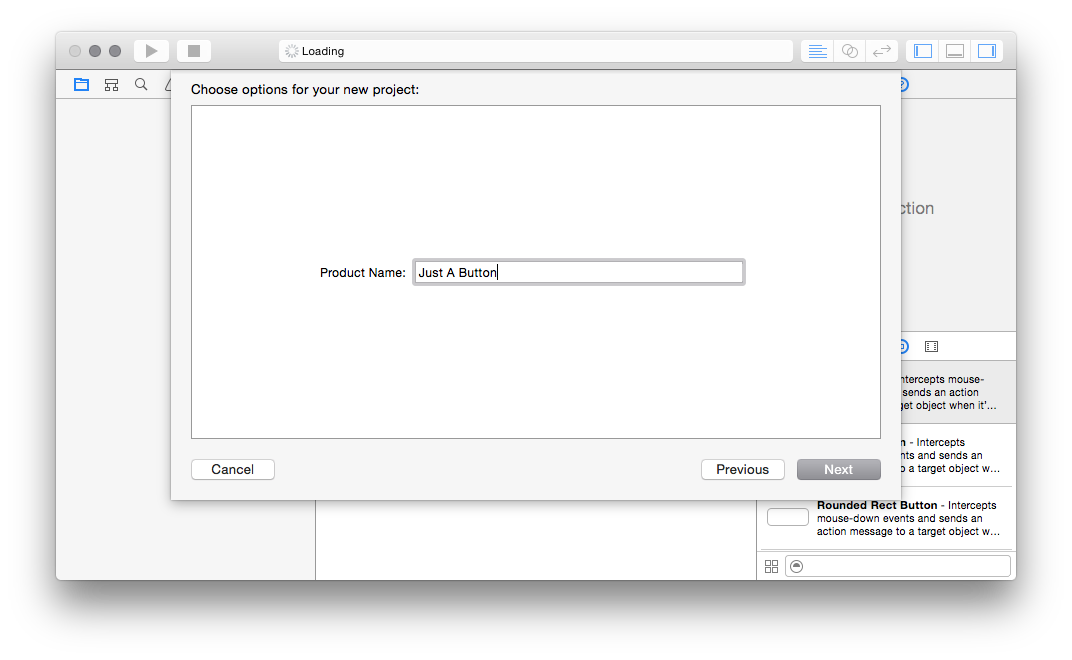

First, you want to make a new, empty Xcode project. So fire up Xcode, go to

File, New, Project, and then:

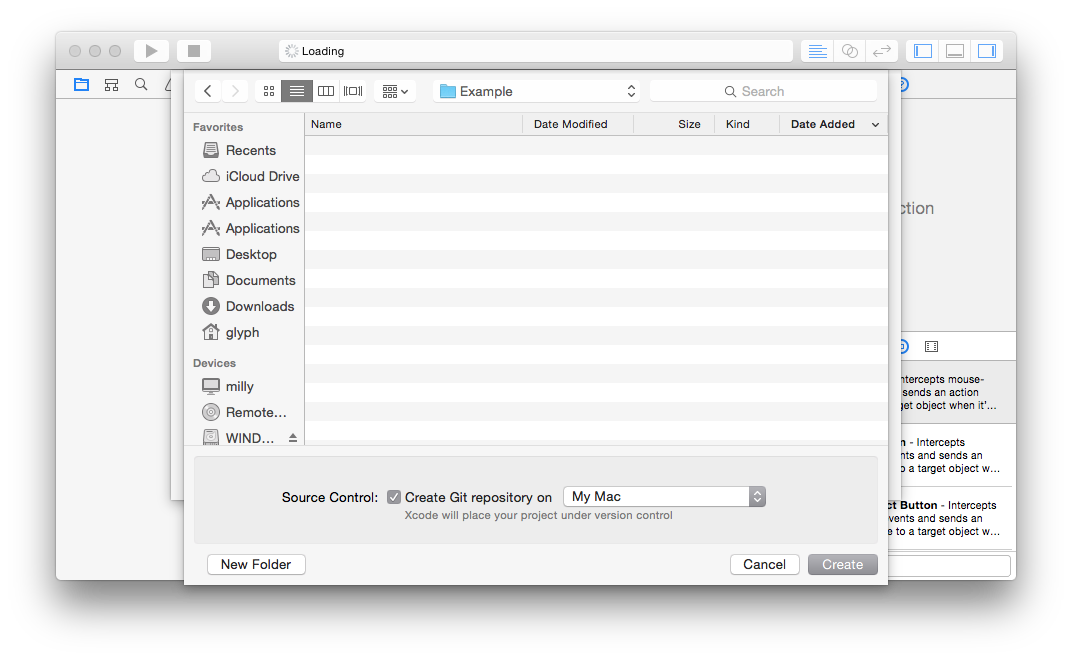

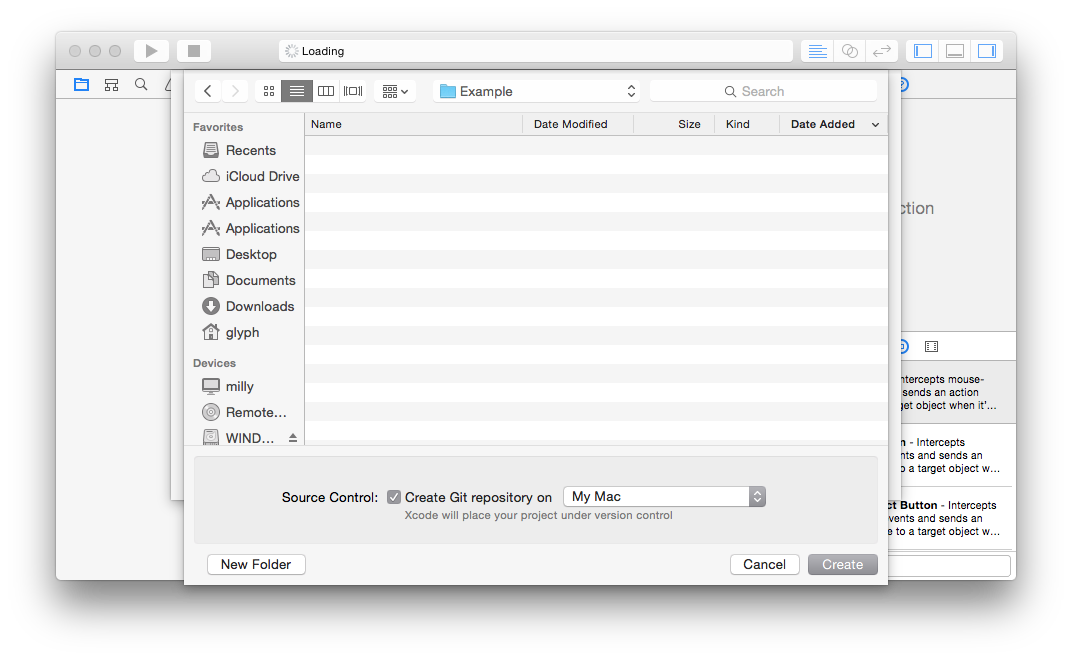

Go ahead and give it a Git repository:

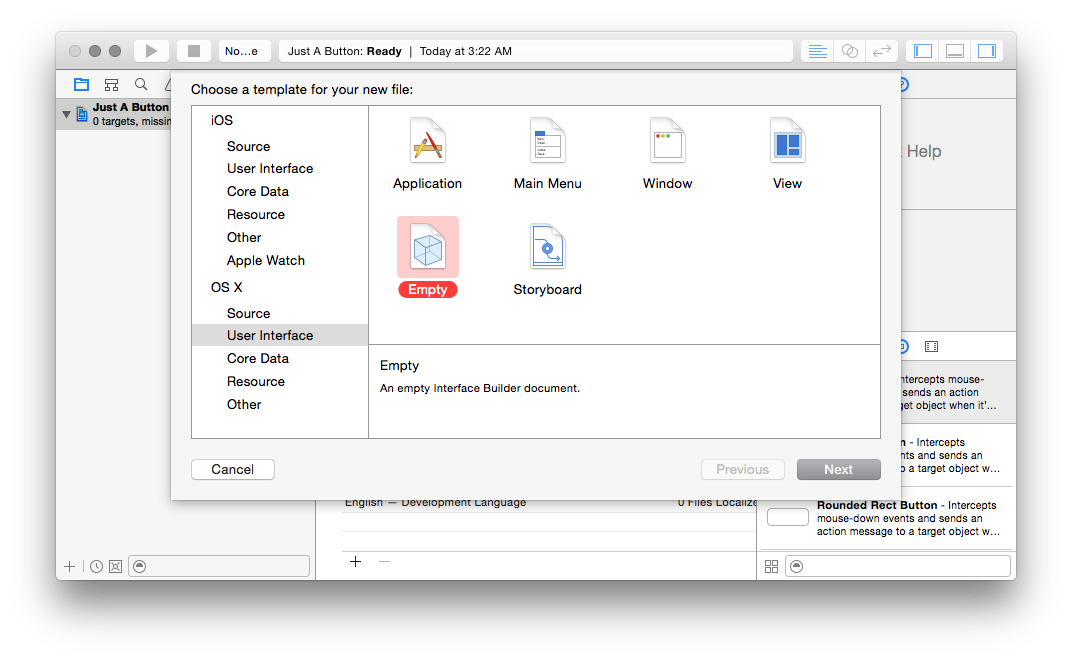

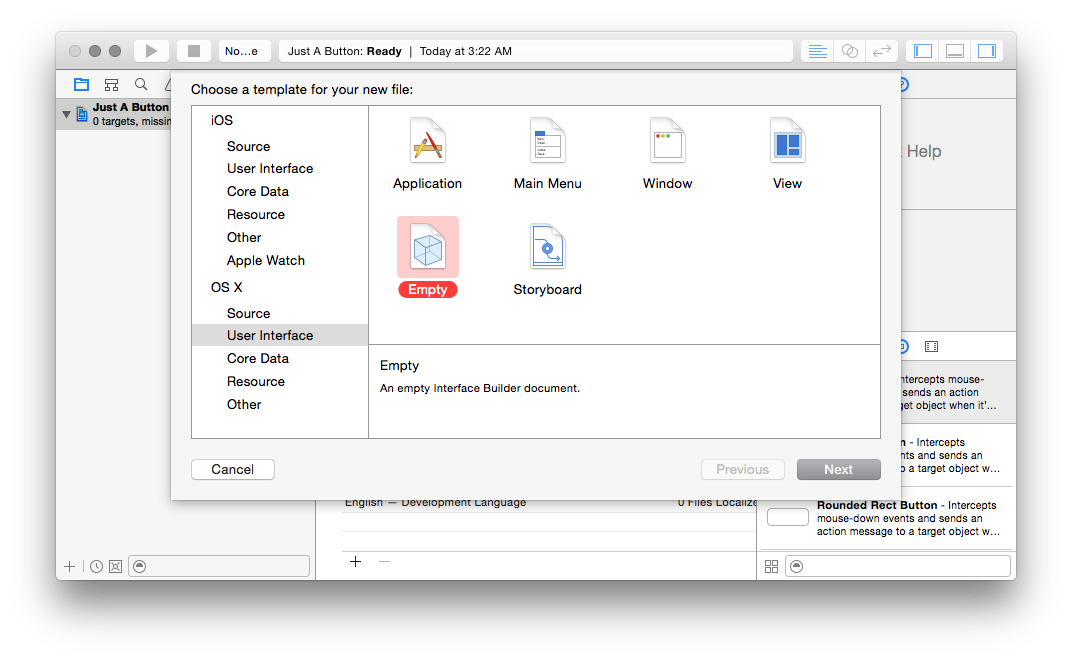

Now that you’ve got a shiny new blank project, you’ll need to create two

resources in it: one, a user interface document, and the other, a Python file.

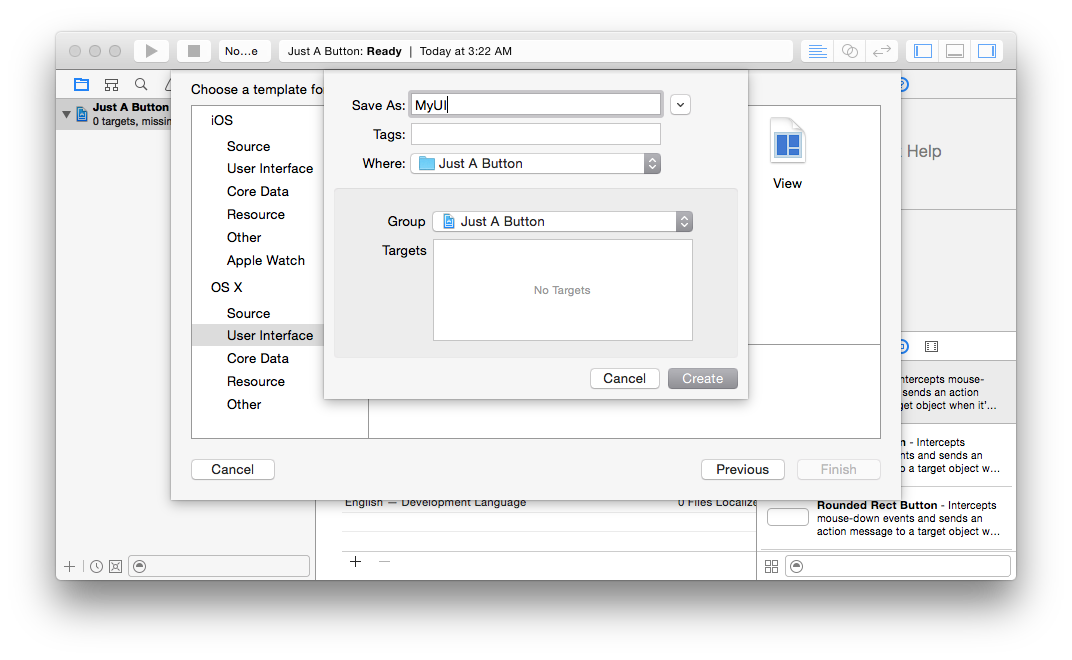

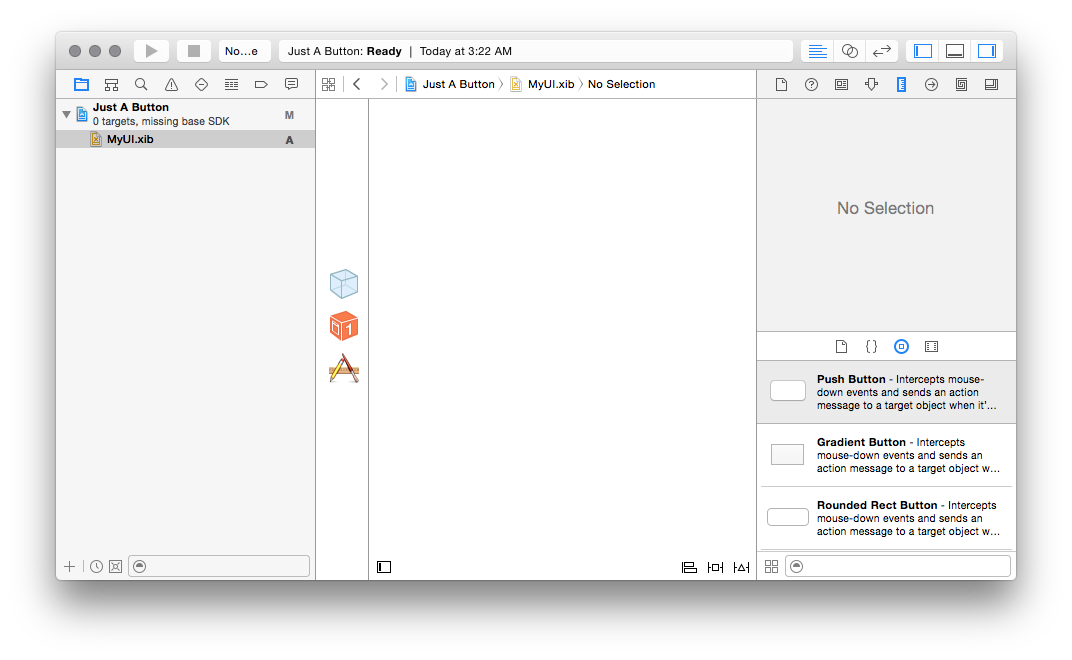

So select File, New, and then choose macOS, User Interface, Empty:

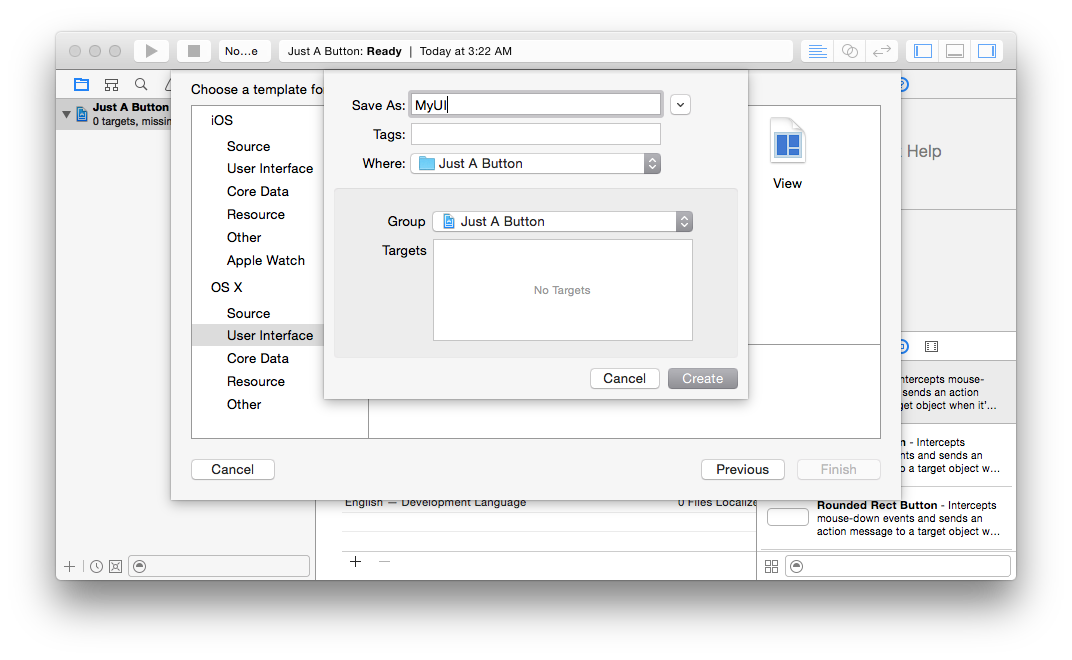

I’m going to call this “MyUI”, but you can call it whatever:

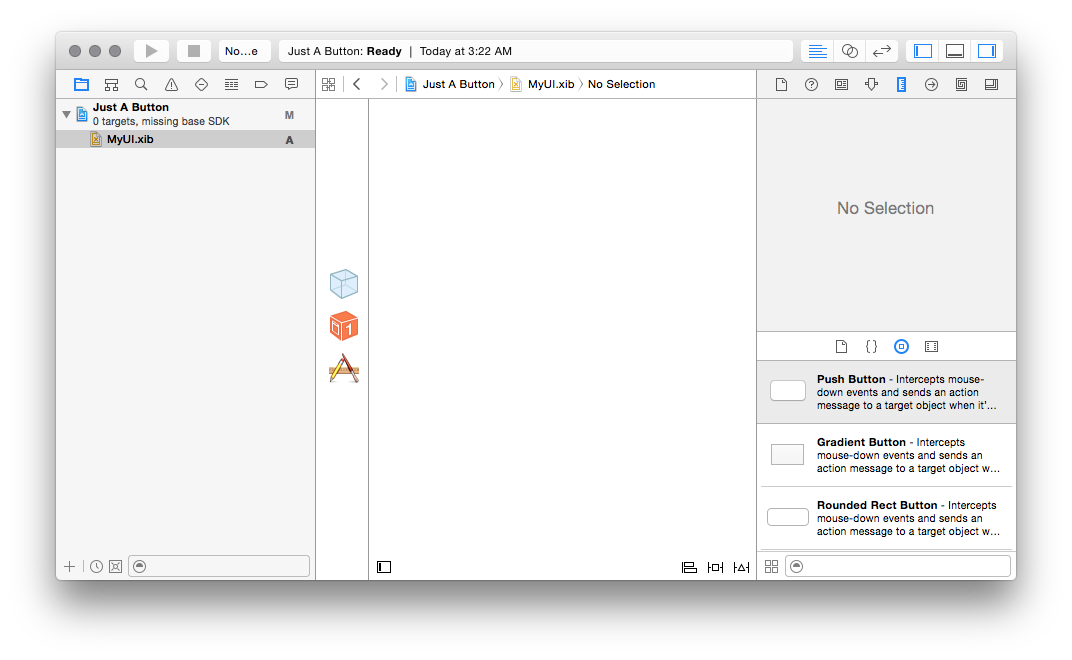

As you can see, this creates a MyUI.xib file in your project, with nothing in

it.

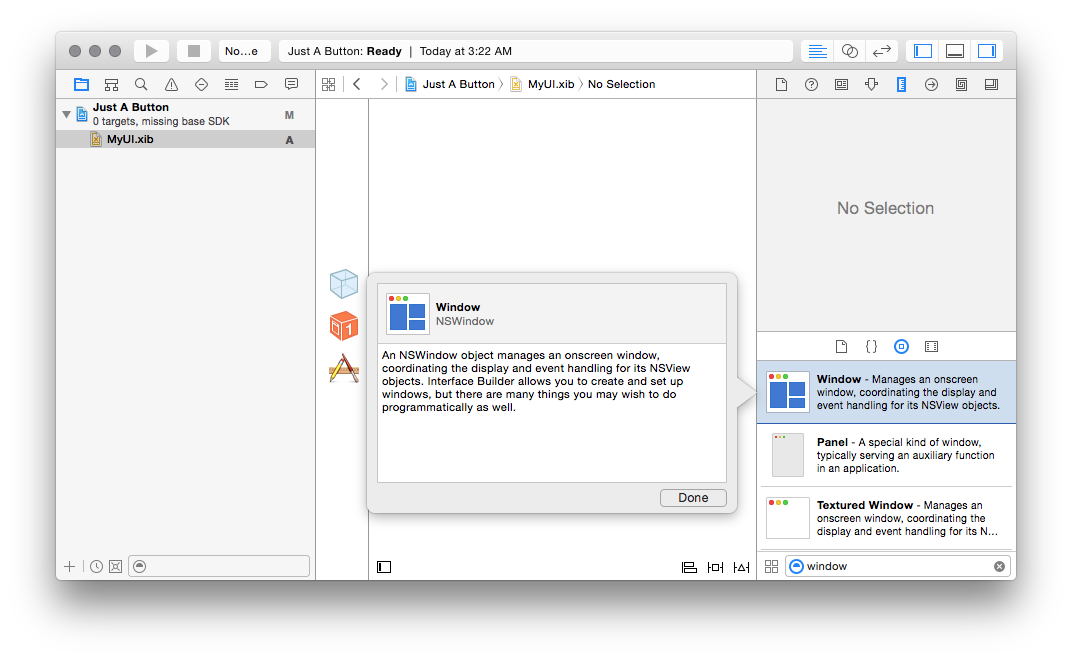

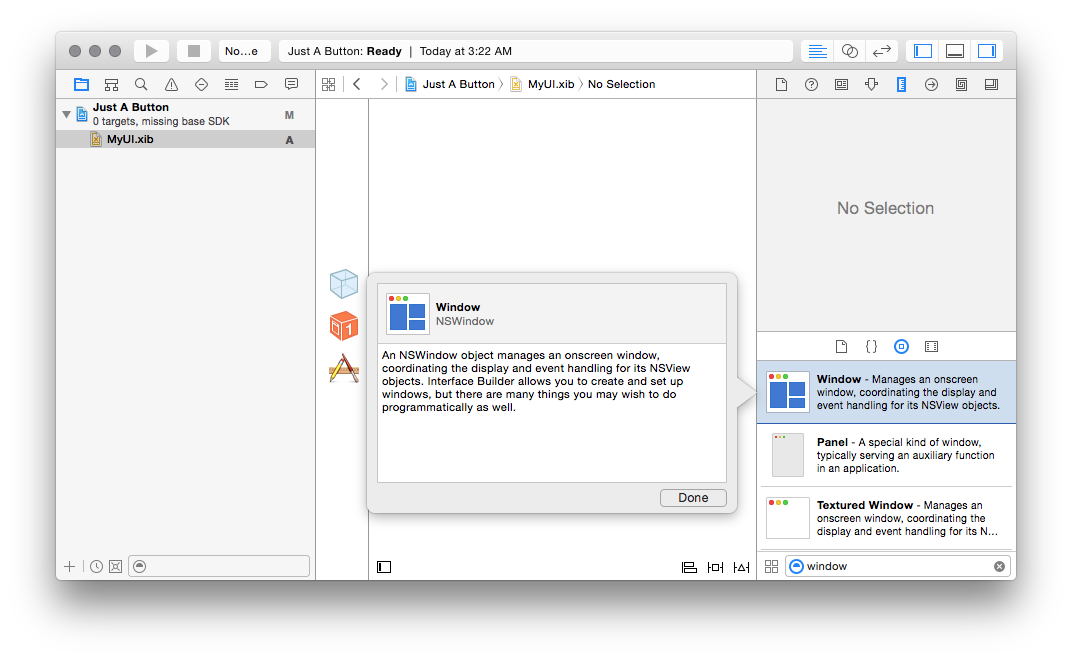

We want to put a window and a button into it, so, let’s start with that.

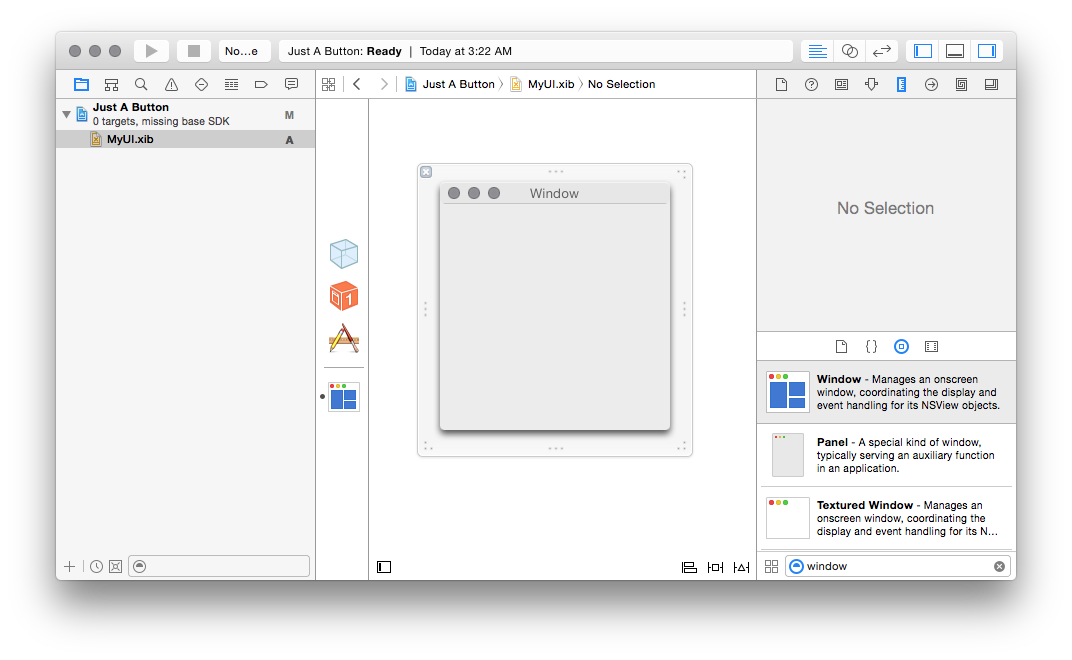

Search for “window” in the bottom right, and drag the “Window” item onto the

canvas in the middle:

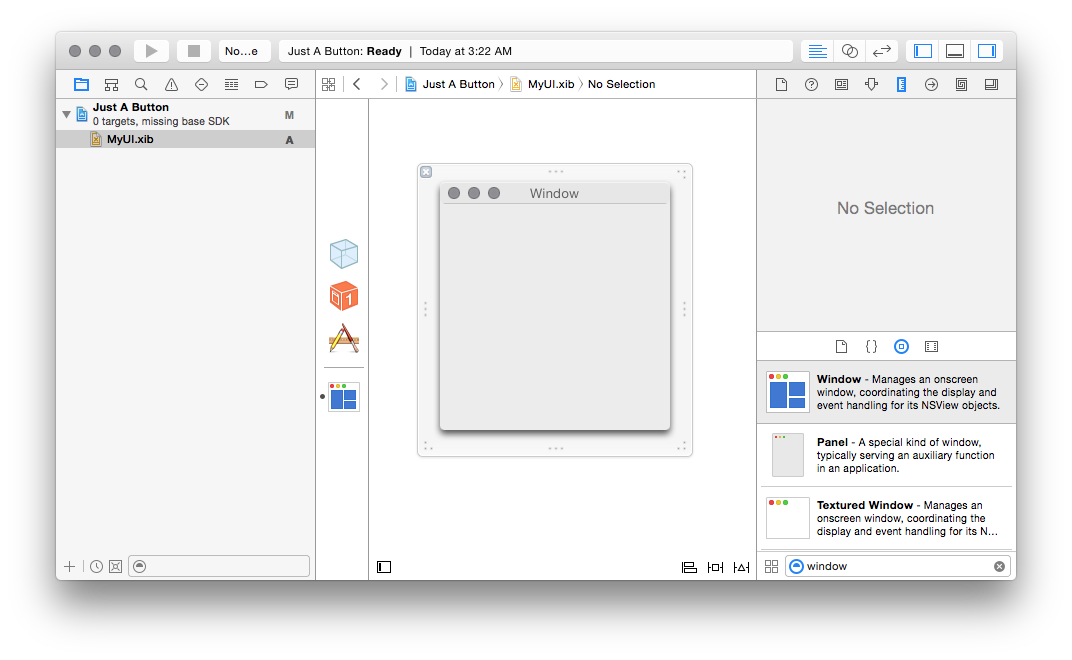

Now we’ve got a UI file which contains a window. How can we display it?

Normally, Xcode sets all this up for you, creating an application bundle, a

build step to compile the .xib into a .nib, to copy it into the appropriate

location, and code to load it for you. But, as we’ve discussed above, we’re

too lazy for all that. Instead, we’re going to create a Python script that

compiles the .xib automatically and then loads it.

You can do this with your favorite text editor. The relevant program looks

like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12 | import os

os.system("ibtool MyUI.xib --compile MyUI.nib")

from Foundation import NSData

from AppKit import NSNib

nib_data = NSData.dataWithContentsOfFile_(u"MyUI.nib")

(NSNib.alloc().initWithNibData_bundle_(nib_data, None)

.instantiateWithOwner_topLevelObjects_(None, None))

from PyObjCTools.AppHelper import runEventLoop

runEventLoop()

|

Breaking this down one step at a time, what it’s doing is:

| import os

os.system("ibtool MyUI.xib --compile MyUI.nib")

|

We run Interface Builder Tool, or ibtool, to convert the xib, which is a

version-control friendly, XML document that Interface Builder can load, into a

nib, which is a binary blob that AppKit can load at runtime. We don’t want

to add a manual build step, so for now we can just have this script do its own

building as soon as it runs.

Next, we need to load the data we just compiled:

| nib_data = NSData.dataWithContentsOfFile_(u"MyUI.nib")

|

This needs to be loaded into an NSData because that’s how AppKit itself

wants it prepared.

Finally, it’s time to load up that window we just drew:

| (NSNib.alloc().initWithNibData_bundle_(nib_data, None)

.instantiateWithOwner_topLevelObjects_(None, None))

|

This loads an NSNib (the “ib” in its name also refers to “Interface

Builder”) with the init... method, and then creates all the objects inside

it - in this case, just our Window object - with the instantiate... method.

(We don’t care about the bundle to use, or the owner of the file, or the top

level objects in the file yet, so we are just leaving those all as None

intentionally.)

Finally, runEventLoop() just runs the event loop, allowing things to be

displayed.

Now, in a terminal, you can run this program by creating a virtualenv, and

doing pip install pyobjc-framework-Cocoa, and then python button.py. You

should see your window pop up - although it will not take focus.

Congratulations, you’ve made a window pop up!

One minor annoyance: you’re probably used to interrupting programs with ^C on

the command line. In this case, the PyObjC helpers catch that signal, so

instead you will need to use ^\ to hard-kill it until we can hook up some

kind of “quit” functionality. This may cause crash dialogs to pop up if you

don’t use virtualenv; you can just ignore them.

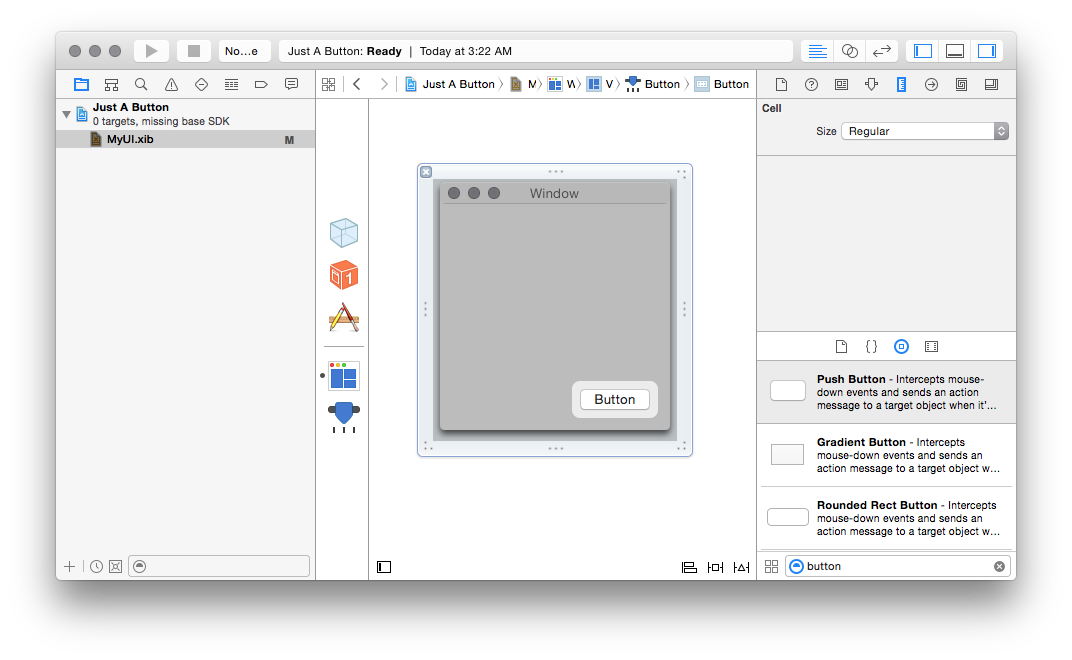

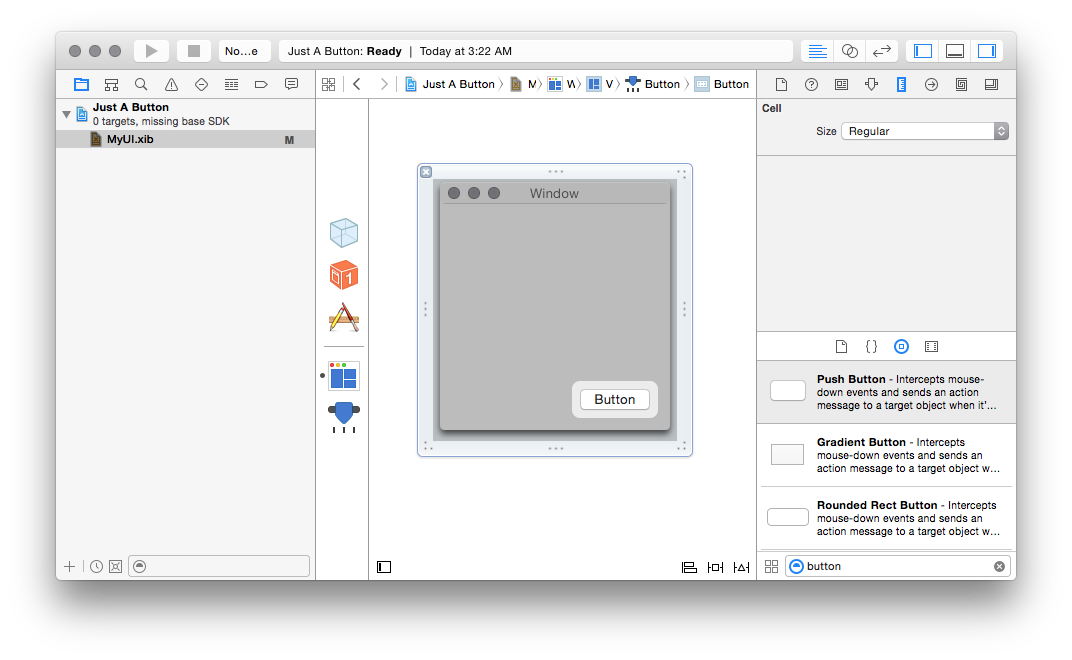

Of course, now that we’ve got a window, we probably want to do something with

it, and this is where things get tricky. First, let’s just create a button;

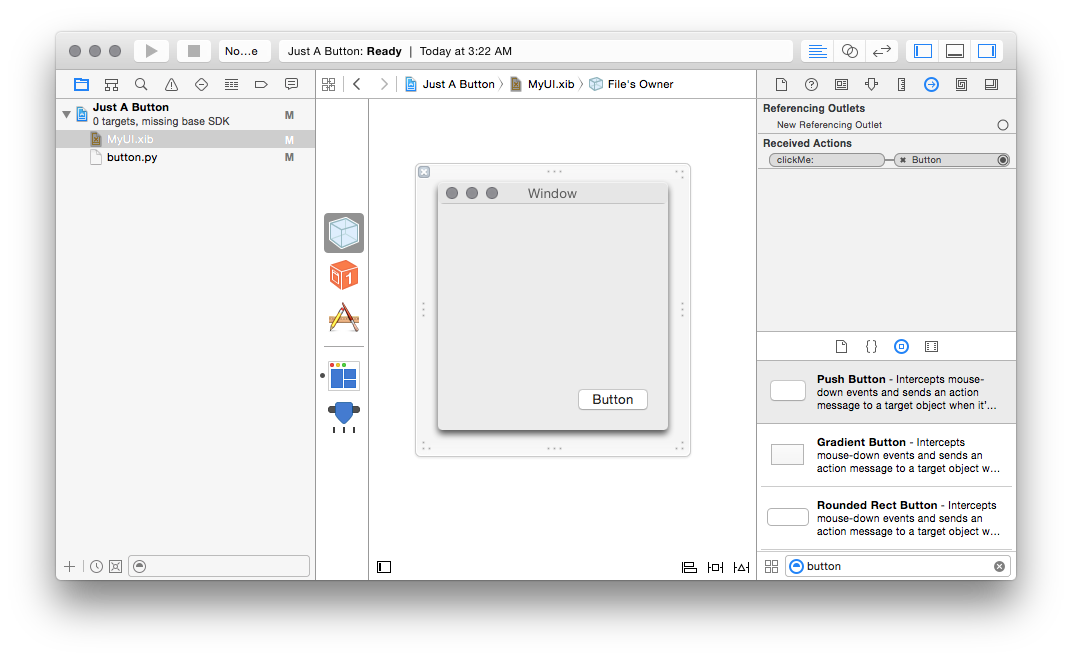

drag the button onto your window, and save the .xib:

And now, the moment of truth: how do we make clicking that button do

anything? If you’ve ever done any Xcode tutorials or written ObjC code, you

know that this is where things get tricky: you need to control-drag an action

to a selector. It figures out which selectors are available by magically

knowing things about your code, and you can’t just click on a thing in the

interface-creation component and say “trust me, this method exists”. Luckily,

although the level of documentation for it these days makes it on par with an

easter egg, Xcode has support for doing this with Python classes just as it

does with Objective C or Swift classes.

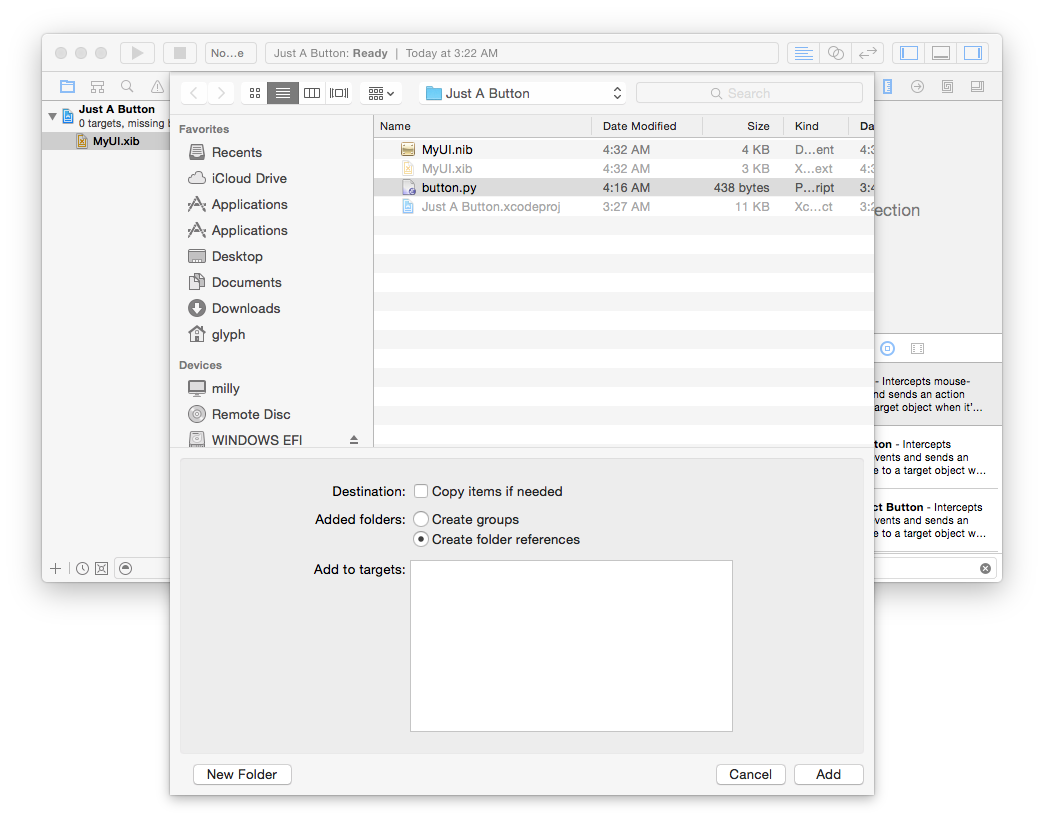

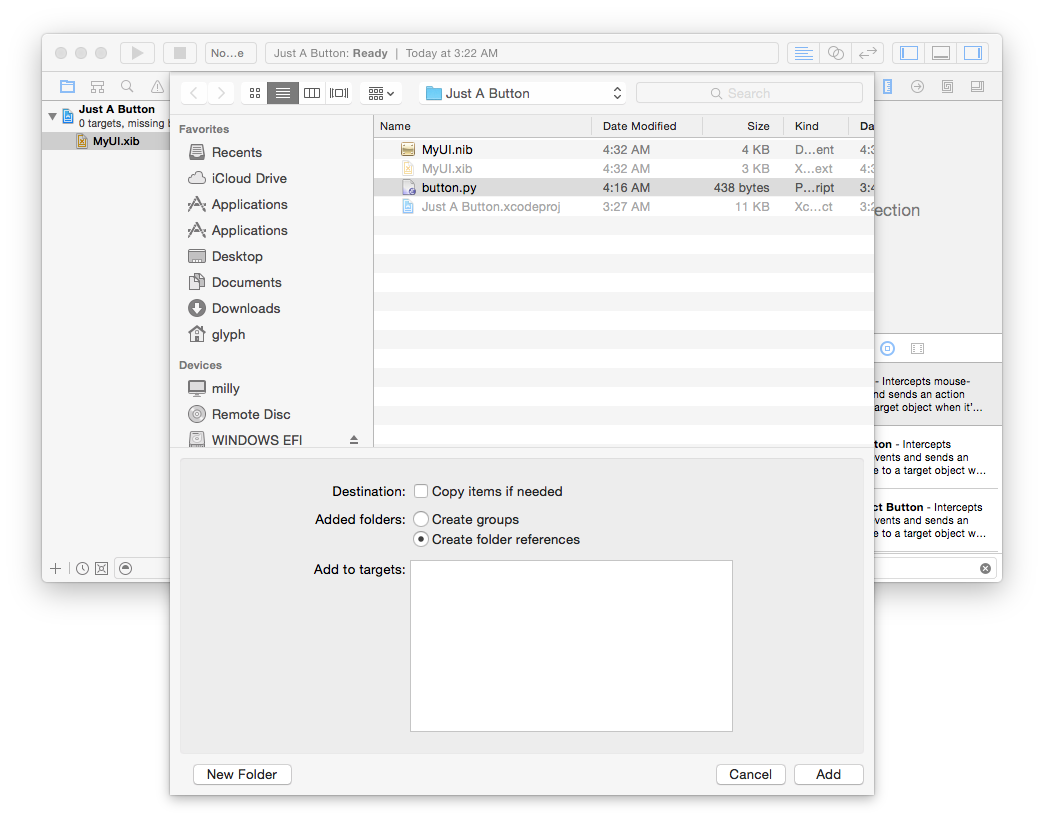

First though, we’ll need to tell Xcode our Python file exists. Go to the

“File” menu, and “Add files to...”, and then select your Python file:

Here’s the best part: you don’t need to use Xcode’s editor at all; Xcode will

watch that file for changes. So keep using your favorite text editor and

change button.py to look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20 | import os

os.system("ibtool MyUI.xib --compile MyUI.nib")

from objc import IBAction

from Foundation import NSObject, NSData

from AppKit import NSNib

class Clicker(NSObject):

@IBAction

def clickMe_(self, sender):

print("Clicked!")

the_clicker = Clicker.alloc().init()

nib_data = NSData.dataWithContentsOfFile_(u"MyUI.nib")

(NSNib.alloc().initWithNibData_bundle_(nib_data, None)

.instantiateWithOwner_topLevelObjects_(the_clicker, None))

from PyObjCTools.AppHelper import runEventLoop

runEventLoop()

|

In other words, add a Clicker subclass of NSObject, give it a clickMe_

method decorated by objc.IBAction, taking one argument, and then make it do

something you can see, like print something. Then, make a global instance of

it, and pass it as the owner parameter to NSNib.

At this point it would probably be good to explain a little about what the

“file’s owner” is and how loading nibs works.

When you instantiate a Nib in AppKit, you are creating a collection of

graphical objects, connected to an object in your program that you construct.

In other words, if you had a program that displayed a Person, you’d have a

Person.nib and a Person class, and each time you wanted to show a Person you’d

instantiate the Nib again with the new Person as the owner of that Nib. In

the interface builder, this is represented by the “file’s owner” placeholder.

I am explaining this because if you’re interested in reading this article,

you’ve probably been interested enough in macOS programming to do something like

the aforementioned

Temperature Converter

tutorial, but such tutorials almost universally just use the single default

“main” nib that gets loaded when the application launches, so although they

show you how to do many different things with UI elements, it’s not clear how

the elements got there. This, here, is how you make new UI elements get

there in the first place.

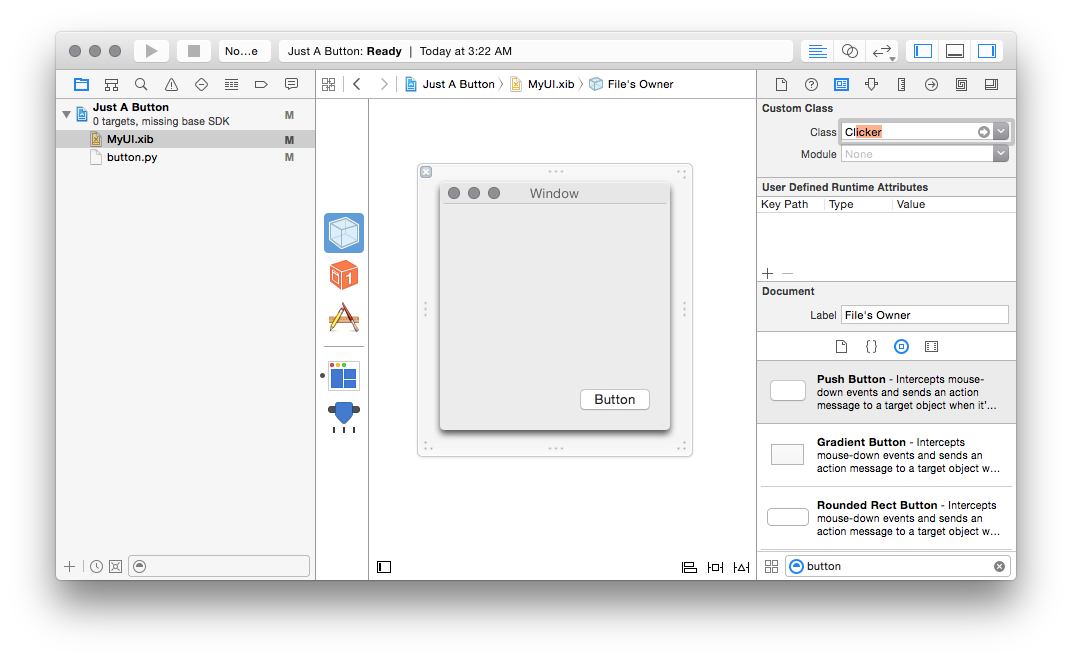

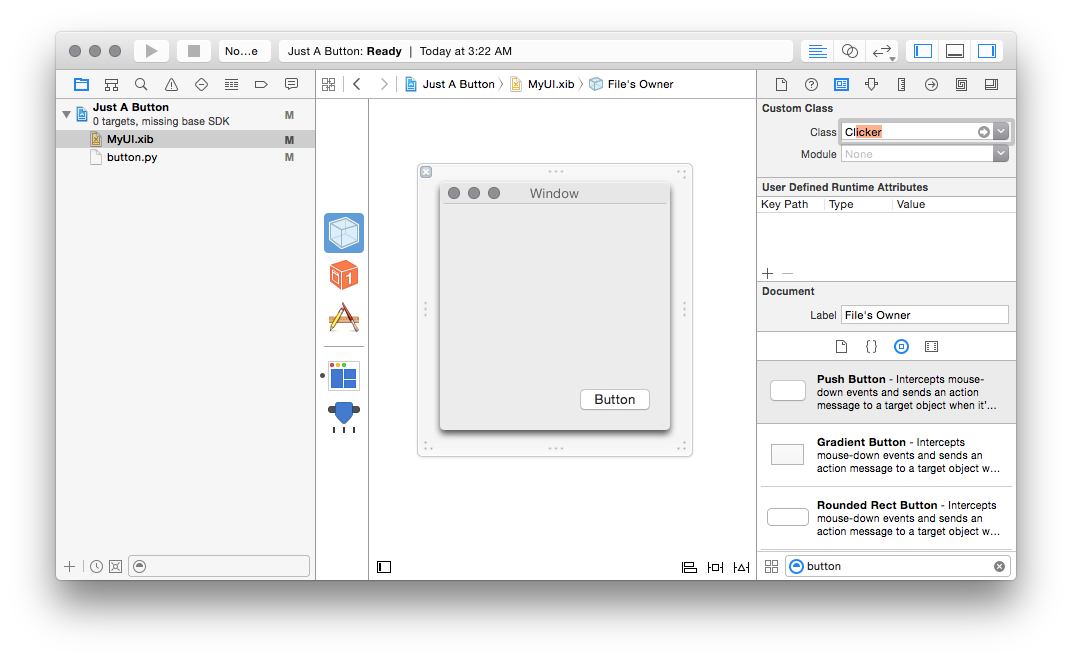

Back to our clicker example: now that we have a class with a method, we need to

tell Xcode that the clicking the button should call that method. So what

we’re going to tell Xcode is that we expect this Nib to be owned by an

instance of Clicker. To do this, go to MyUI.xib and select the “File’s

Owner” (the thing that looks like a transparent cube), to to the “Identity

Inspector” (the tiny icon that looks like a driver’s license on the right) and

type “Clicker” in the “Class” field at the top.

If you’ve properly added button.py to your project and declared that class

(as an NSObject), it should automatically complete as you start typing the

name:

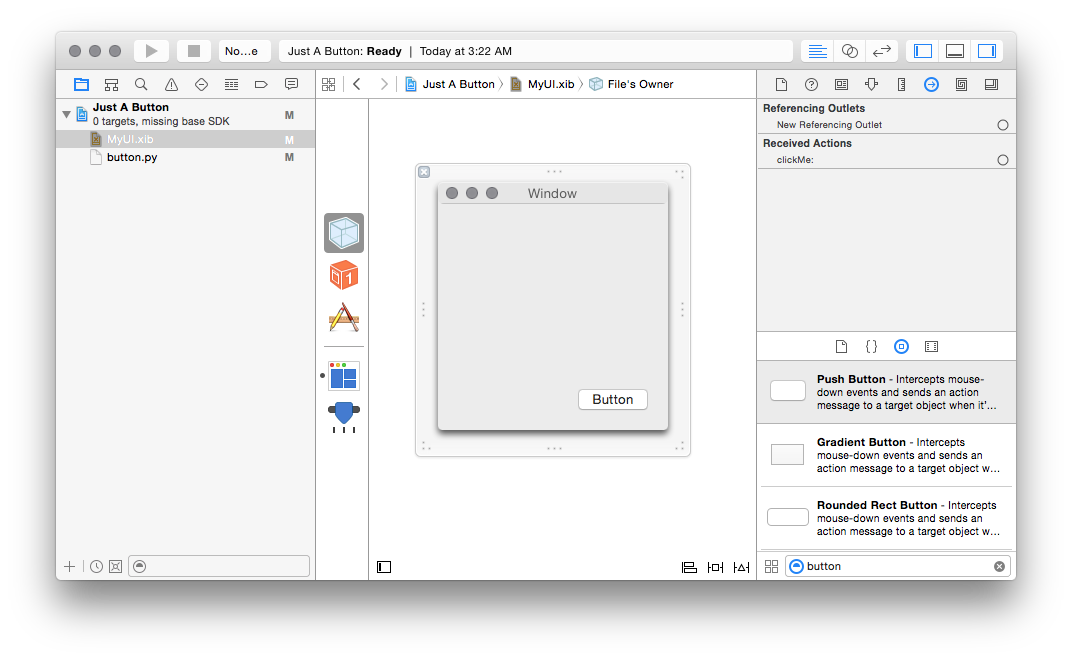

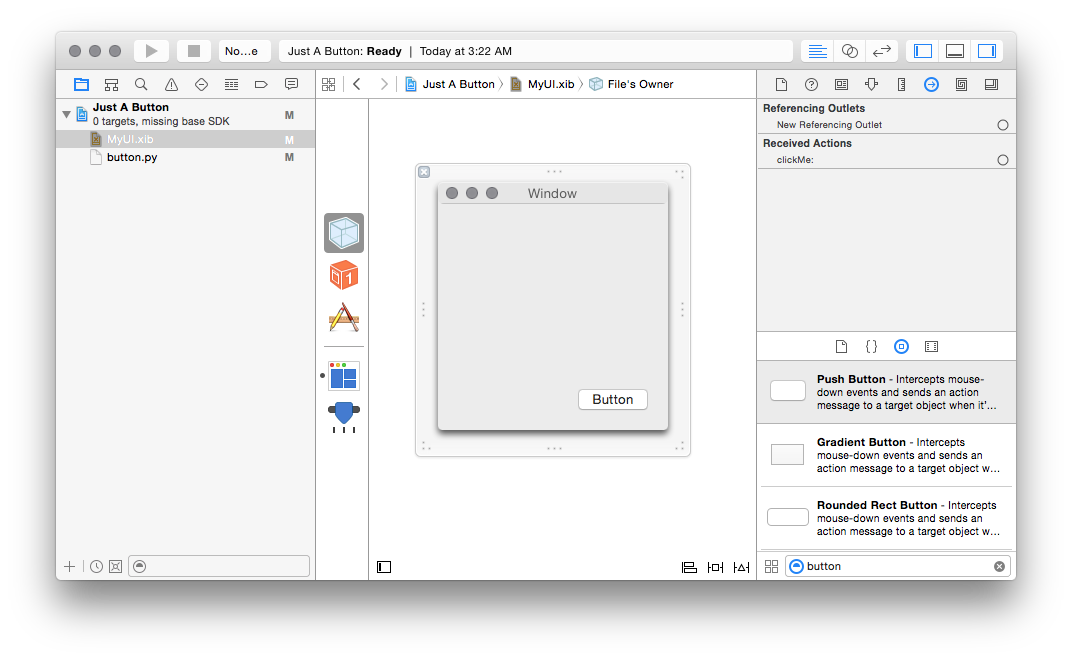

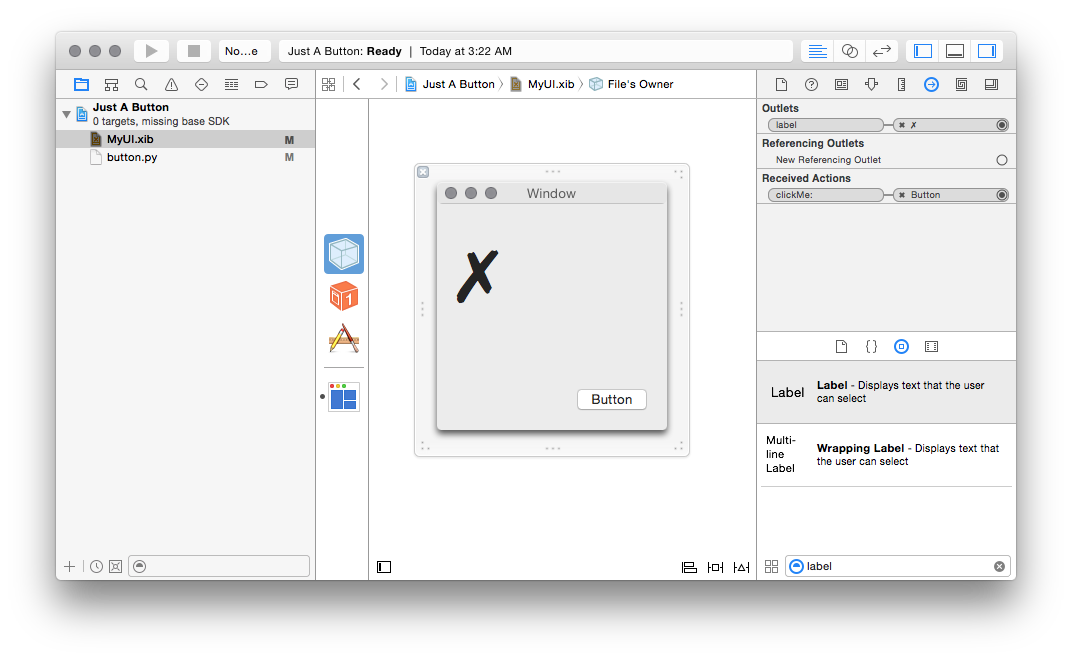

Now you need to connect your clickMe action to the button you already

created. If you’ve properly declared your method as an IBAction, you should

see it in the list of “received actions” in the “Connections Inspector” of the

File’s Owner (the tiny icon that looks like a right-pointing arrow in a

circle):

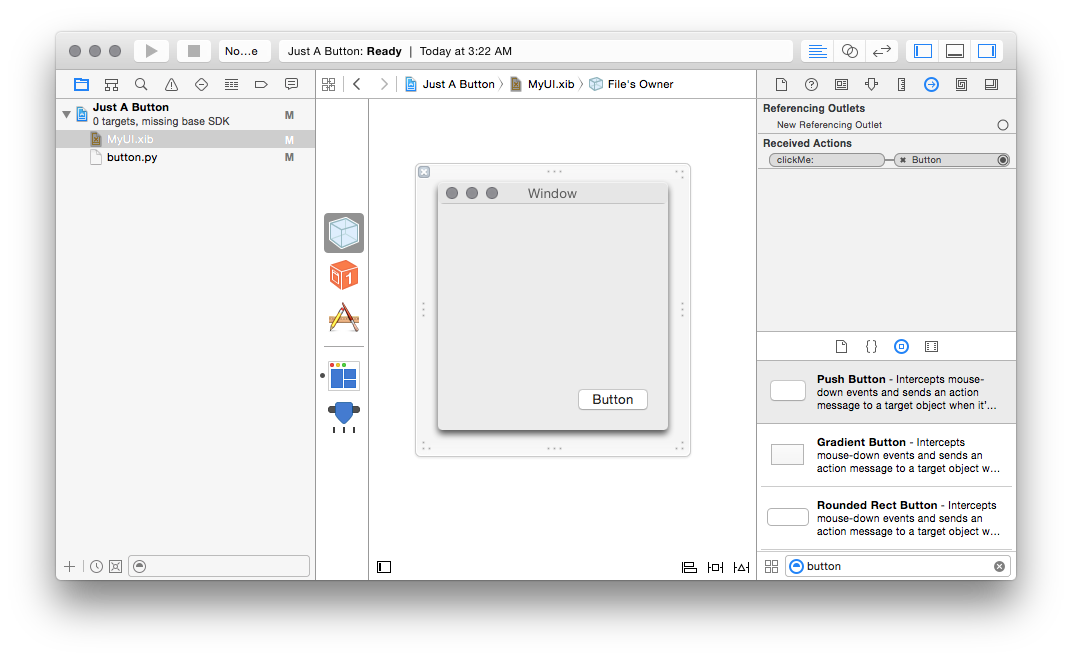

Drag from the circle to the right of the clickMe: method there to the button

you’ve created, and you should see the connection get formed:

If you save your xib at this point and re-run your python file, you should be

able to click on the button and see something happen.

Finally, we want to be able to not just get inputs from the GUI, but also

produce outputs. To do this, we want to populate an outlet on our Clicker

class with a pointer to an object in the Nib. We can do this by declaring a

variable as an objc.IBOutlet(); simply add a from objc import IBOutlet, and

change Clicker to read:

| class Clicker(NSObject):

label = IBOutlet()

@IBAction

def clickMe_(self, sender):

self.label.setStringValue_(u"\N{CHECK MARK}")

|

In case you’re wondering where setStringValue_ comes from, it’s a method on NSTextField, since labels are NSTextFields.

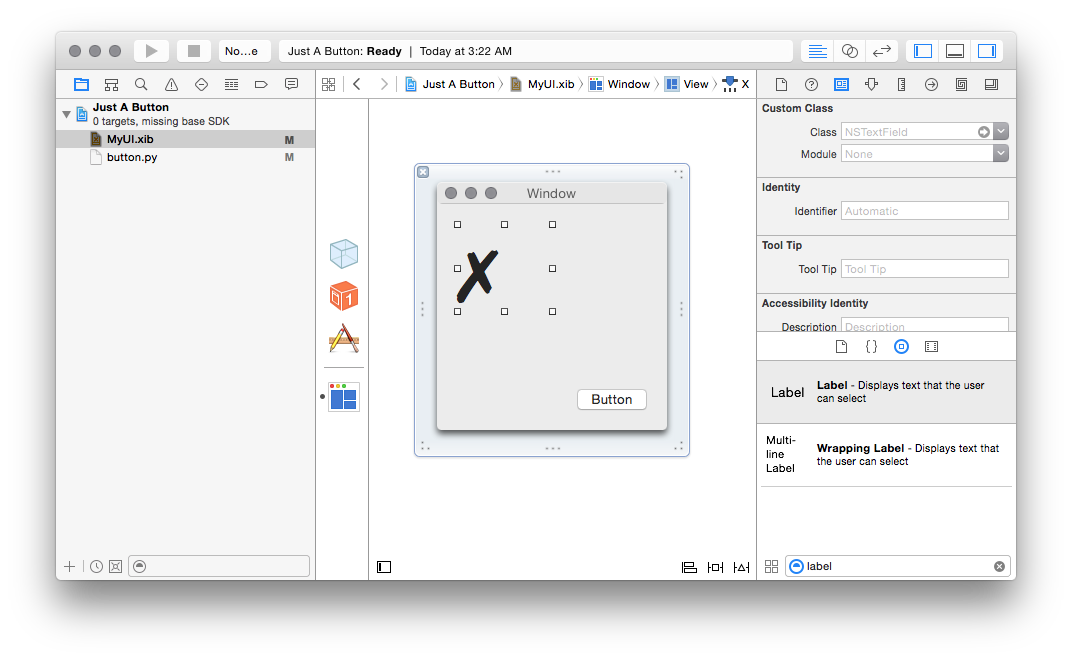

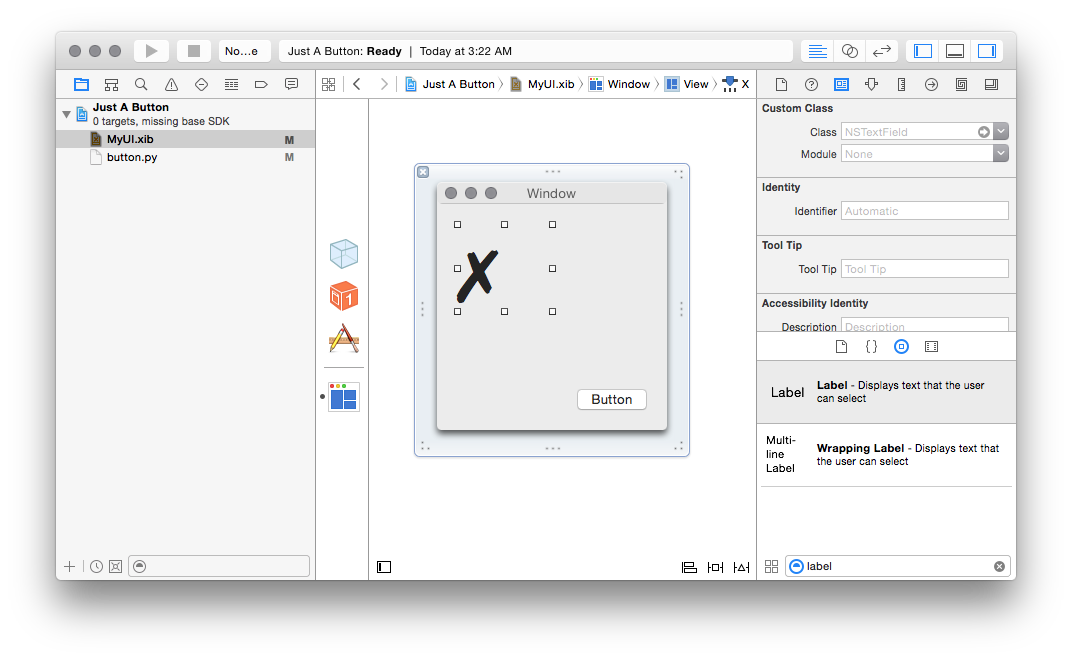

Then we can place a label into our xib; and we can see it is in fact an

NSTextField in the Identity Inspector:

I’ve pre-filled mine out with a unicode “BALLOT X” character, for style points.

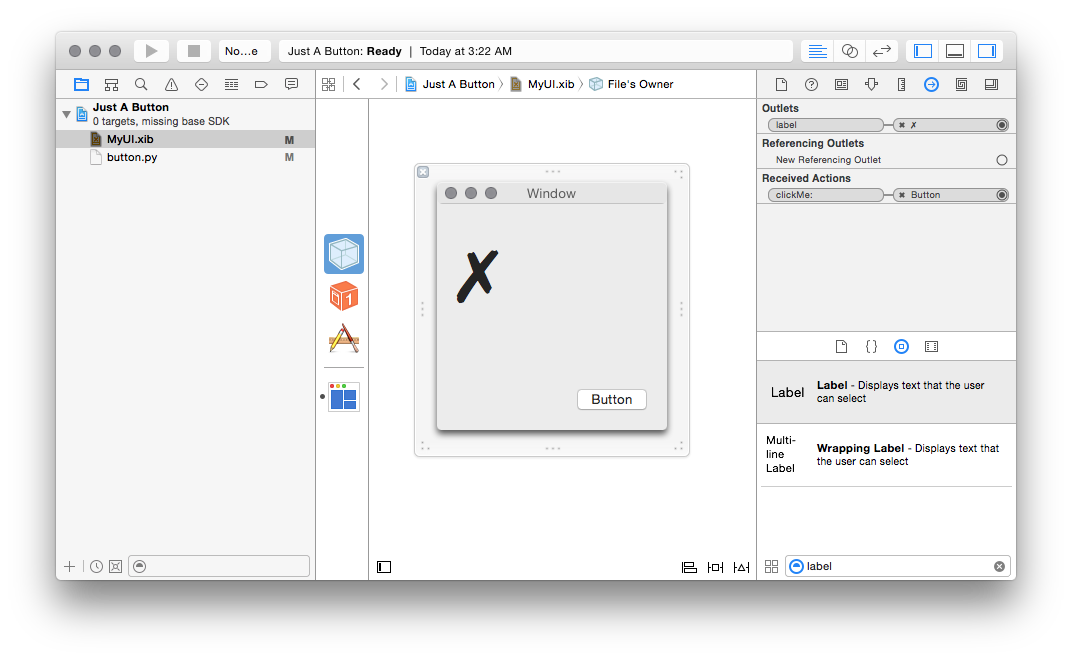

Then, we just need to make sure that the label attribute of Clicker

actually points at this value; once again, select the File’s Owner, the

Connections Inspector, and (if you declared your IBOutlet correctly), you

should see a new “label” outlet. Drag the little circle to the right of that

outlet, to the newly-created label object, and you should see the linkage in

the same way the action was linked:

And there you have it! Now you have an application that can open a window,

take input, and display output.

This is, as should be clear by now, not really the preferred way of making an

application for macOS. There’s no app bundle, so there’s nothing to code-sign.

You’ll get weird behavior in certain cases; for example, as you’ve probably

already noticed, the window doesn’t come to the front when you launch the app

like you might expect it to. But, if you’re a Python programmer, this should

provide you with a quick scratch pad where you can test ideas, learn about how

interface builder works, and glue a UI to existing Python code quickly before

wrestling with complex integration and distribution issues.

Speaking of interfacing with existing Python code, of course you wouldn’t come

to this blog and expect to get technical content without just a little bit

of Twisted in it. So here’s how you hook up Twisted to an macOS GUI: instead of

runEventLoop, you need to run your application like this:

| # Before importing anything else...

from PyObjCTools.AppHelper import runEventLoop

from twisted.internet.cfreactor import install

reactor = install(runner=runEventLoop)

# ... then later, when you want to run it ...

reactor.run()

|

In your virtualenv, you’ll want to pip install 'twisted[macos_platform]' to get

all the goodies for macOS, including the GUI integration. Since all Twisted

callbacks run on the main UI thread, you don’t need to know anything special to

do stuff; you can call methods on whatever UI objects you have handy to make

changes to them.

Finally, although I definitely don’t have room in this post to talk about all

the edge cases here, I will address two particularly annoying ones; often if

you’re writing a little app like this, you really want it to take keyboard

focus, and by default this window will come up in the background. To fix that,

you can do this right before starting the main loop:

| from AppKit import NSApplication, NSApplicationActivationPolicyAccessory

app = NSApplication.sharedApplication()

app.setActivationPolicy_(NSApplicationActivationPolicyAccessory)

app.activateIgnoringOtherApps_(True)

|

And also, closing the window won’t quit the application, which might be pretty

annoying if you want to get back to using your terminal, so a quick fix for

that is:

| class QuitWhenClosed(NSObject):

def applicationShouldTerminateAfterLastWindowClosed_(self, app):

return True

app.setDelegate_(QuitWhenClosed.alloc().init().retain())

|

(the “retain” is necessary because ObjC is not a garbage collected language,

and app.delegate is a weak reference, so the QuitWhenClosed would be

immediately freed (and there would be a later crash) if you didn’t hold it in a

global variable or call retain() on it.)

You might have

other problems

with this technique, and this post definitely can’t fit solutions to all of

them, but now that you can load a nib, create classes that interface builder

can understand, and run a Twisted main loop, you should be able to use the

instructions in other tutorials and resources relatively straightforwardly.

Happy hacking!

(Thanks to everyone who helped with this post. Of course my errors are

entirely my own, but thanks especially to Ronald Oussoren for his tireless work

on pyObjC and py2app over the years, as well as to Mark Eichin and Amber Brown

for some proofreading and feedback before this was posted.)