Sometimes, sea sickness is caused by a sort of confusion. Your inner ear can

feel the motion of the world around it, but because it can’t see the outside

world, it can’t reconcile its visual input with its

proprioceptive input, and the

result is nausea.

This is why it helps

to see the horizon.

If you can see the horizon, your eyes will talk to your inner ears by way of your brain, they will realize that everything is where it should be, and that everything will be OK.

As a result, you’ll stop feeling sick.

I have a sort of motion sickness too, but it’s not seasickness. Luckily, I do

not experience nausea due to moving through space. Instead, I have a sort of

temporal motion sickness. I feel ill, and I can’t get anything done, when I

can’t see the time horizon.

I think I’m going to need to explain that a bit, since I don’t mean

the end of the current fiscal quarter.

I realize this doesn’t make sense yet. I hope it will, after a bit of an

explanation. Please bear with me.

Time management gurus often advise that it is “good” to break up large,

daunting tasks into small, achievable chunks. Similarly, one has to schedule

one’s day into dedicated portions of time where one can concentrate on specific

tasks. This appears to be common sense. The most common enemy of productivity

is procrastination. Procrastination happens when you are working on the wrong

thing instead of the right thing. If you consciously and explicitly allocate

time to the right thing, then chances are you will work on the right thing.

Problem solved, right?

Except, that’s not quite how work, especially creative work, works.

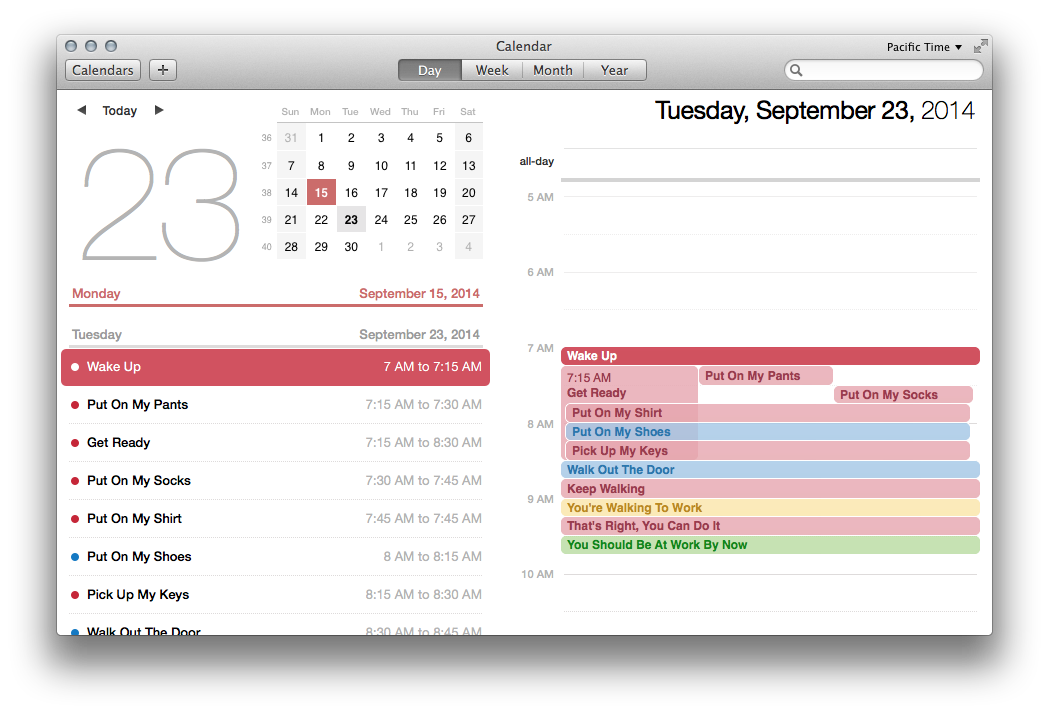

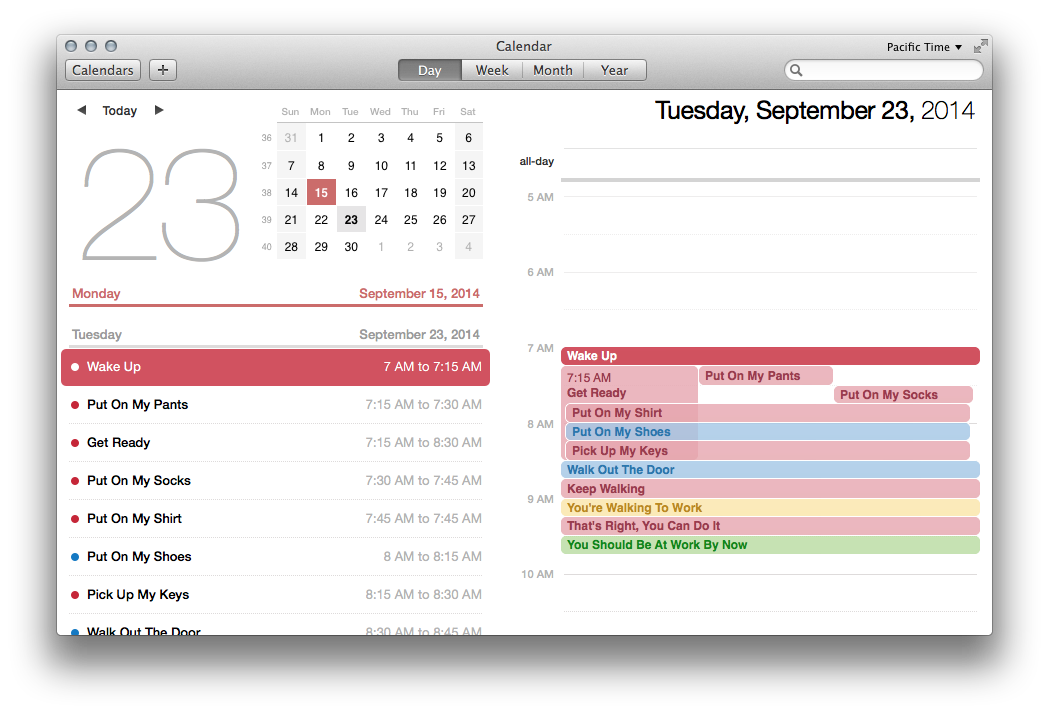

I try to be “good”. I try to classify all of my tasks. I put time on my

calendar to get them done. I live inside little boxes of time that tell me

what I need to do next. Sometimes, it even works. But more often than not,

the little box on my calendar feels like a little cage. I am inexplicably,

involuntarily, haunted by disruptive visions of the future that happen when

that box ends.

Let me give you an example.

Let’s say it’s 9AM Monday morning and I have just arrived at work. I can see

that at 2:30PM, I have a brief tax-related appointment. The hypothetical

person doing my hypothetical taxes has an office that is a 25 minute

hypothetical walk away, so I will need to leave work at 2PM sharp in order to

get there on time. The appointment will last only 15 minutes, since I just

need to sign some papers, and then I will return to work. With a 25 minute

return trip, I should be back in the office well before 4, leaving me plenty of

time to deal with any peripheral tasks before I need to leave at 5:30. Aside

from an hour break at noon for lunch, I anticipate no other distractions during

the day, so I have a solid 3 hour chunk to focus on my current project in the

morning, an hour from 1 to 2, and an hour and a half from 4 to 5:30. Not an

ideal day, certainly, but I have plenty of time to get work done.

The problem is, as I sit down in front of my nice, clean, empty text editor to

sketch out my excellent programming ideas with that 3-hour chunk of time, I

will immediately start thinking about how annoyed I am that I’m going to get

interrupted in 5 and a half hours. It consumes my thoughts. It annoys me. I

unconsciously attempt to soothe myself by checking email and getting to a nice,

refreshing inbox zero. Now it’s 9:45. Well, at least my email is done. Time

to really get to work. But now I only have 2 hours and 15 minutes, which is

not as nice of an uninterrupted chunk of time for a deep coding task. Now I’m

even more annoyed. I glare at the empty window on my screen. It glares back.

I spend 20 useless minutes doing this, then take a 10-minute coffee break to

try to re-set and focus on the problem, and not this silly tax meeting. Why

couldn’t they just mail me the documents? Now it’s 10:15, and I still haven’t

gotten anything done.

By 10:45, I manage to crank out a couple of lines of code, but the fact that

I’m going to be wasting a whole hour with all that walking there and walking

back just gnaws at me, and I’m slogging through individual test-cases,

mechanically filling docstrings for the new API and for the tests, and not

really able to synthesize a coherent, holistic solution to the overall problem

I’m working on. Oh well. It feels like progress, albeit slow, and some days

you just have to play through the pain. I struggle until 11:30 at which point

I notice that since I haven’t been able to really think about the big picture,

most of the test cases I’ve written are going to be invalidated by an API

change I need to make, so almost all of the morning’s work is useless. Damn

it, it’s 2014, I should be able to just fill out the forms online or

something, having to physically carry an envelope with paper in it ten

blocks is just ridiculous.

Maybe I could get my falcon to deliver it for me.

It’s 11:45 now, so I’m not going to get anything useful done before lunch. I

listlessly click on stuff on my screen and try to relax by thinking about my

totally rad falcon until it’s time

to go. As I get up, I glance at my phone and see the reminder for the tax

appointment.

Wait a second.

The appointment has today’s date, but the subject says “2013”. This was just

some mistaken data-entry in my calendar from last year! I don’t have an

appointment today! I have nowhere to be all afternoon.

For pointless anxiety over this fake chore which never even actually happened,

a real morning was ruined. Well, a hypothetical real morning; I have never

actually needed to interrupt a work day to walk anywhere to sign tax paperwork.

But you get the idea.

To a lesser extent, upcoming events later in the week, month, or even year

bother me. But the worst is when I know that I have only 45 minutes to get

into a task, and I have another task booked up right against it. All this

trying to get organized, all this carving out uninterrupted time on my

calendar, all of this trying to manage all of my creative energies and marshal

them at specific times for specific tasks, annihilates itself when I start

thinking about how I am eventually going to have to stop working on the

seemingly endless, sprawling problem set before me.

The horizon I need to see is the infinite time available before me to do all

the thinking I need to do to solve whatever problem has been set before me. If I want to write a paragraph of an essay, I need to see enough time to write the whole thing.

Sometimes - maybe even, if I’m lucky, increasingly frequently - I manage to

fool myself. I hide my calendar, close my eyes, and imagine an undisturbed

millennium in front of my text editor ... during which I may address some

nonsense problem with malformed utf-7 in mime headers.

... during which I can complete a long and detailed email about process

enhancements in open source.

... during which I can write a lengthy blog post about my productivity-related

neuroses.

I imagine that I can see all the way to the distant horizon

at the end of time, and that there is nothing between me

and it except dedicated, meditative concentration.

That is on a good day. On a bad day, trying to hide from this anxiety

manifests itself in peculiar and not particularly healthy ways. For one thing,

I avoid sleep. One way I can always extend the current block of time allocated

to my current activity is by just staying awake a little longer. I know this

is basically the wrong way to go about it. I know that it’s bad for me, and

that it is almost immediately counterproductive. I know that ... but it’s

almost 1AM and I’m still typing. If I weren’t still typing right now, instead

of sleeping, this post would never get finished, because I’ve spent far too

many evenings looking at the unfinished, incoherent draft of it and saying to

myself, "Sure, I’d love to work on it, but I have a dentist’s appointment in

six months and that is going to be super distracting; I might as well not get

started".

Much has been written about the deleterious effects of interrupting creative thinking.

But what interrupts me isn’t an interruption; what distracts me isn’t even a

distraction. The idea of a distraction is distracting; the specter of a

future interruption interrupts me.

This is the part of the article where I wow you with my

life hack,

right? Where I reveal the

one weird trick

that will make productivity gurus hate you? Where you won’t believe what

happens next?

Believe it: the surprise here is that this is not a set-up for some choice

productivity wisdom or a sales set-up for my new book. I have no idea how to

solve this problem. The best I can do is that thing I said above about closing

my eyes, pretending, and concentrating. Honestly, I have no idea even if anyone

else suffers from this, or if it’s a unique neurosis. If a reader would be

interested in letting me know about their own

experiences, I might update this article to share some ideas, but for now it is

mostly about sharing my own vulnerability and not about any particular

solution.

I can share one lesson, though. The one thing that this peculiar anxiety has

taught me is that productivity “rules” are not revealed divine truth. They are

ideas, and those ideas have to be evaluated exclusively on the basis of their

efficacy, which is to say, on the basis of how much stuff that you want to get

done that they help you get done.

For now, what I’m trying to do is to un-clench the fearful, spasmodic fist in

my mind that gripping the need to schedule everything into these small boxes

and allocate only the time that I “need” to get something specific done.

Maybe the only way I am going to achieve anything of significance is with

opaque, 8-hour slabs of time with no more specific goal than “write some words,

maybe a blog post, maybe some fiction, who knows” and “do something

work-related”. As someone constantly struggling to force my own fickle mind to

accomplish any small part of my ridiculously ambitions creative agenda, it’s

really hard to relax and let go of anything which might help, which might

get me a little further a little faster.

Maybe I should be trying to schedule my time into tiny little blocks. Maybe

I’m just doing it wrong somehow and I just need to be harder on myself,

madder at myself, and I really can get the blood out of this particular stone.

Maybe it doesn’t matter all that much how I schedule my own time because

there’s always some upcoming distraction that I can’t control, and I just

need to get better at meditating and somehow putting them out of my mind

without really changing what goes on my calendar.

Maybe this is just as productive as I get, and I’ll still be fighting this

particular fight with myself when I’m 80.

Regardless, I think it’s time to let go of that fear and try something a little

different.