Facebook — and by extension, most of Silicon Valley — rightly gets a lot of

shit

for its

old

motto, “Move Fast and Break Things”.

As a general principle for living your life, it is obviously terrible advice,

and it leads to a lot of the horrific

outcomes

of Facebook’s business.

I don’t want to be an apologist for Facebook. I also do not want to excuse the

worldview that leads to those kinds of outcomes. However, I do want to try to

help laypeople understand how software engineers—particularly those situated

at the point in history where this motto became popular—actually meant by it.

I would like more people in the general public to understand why, to engineers,

it was supposed to mean roughly the same thing as Facebook’s newer,

goofier-sounding “Move fast with stable infrastructure”.

Move Slow

In the bad old days, circa 2005, two worlds within the software industry were

colliding.

The old world was the world of integrated hardware/software companies, like IBM

and Apple, and shrink-wrapped software companies like Microsoft and

WordPerfect. The new world was software-as-a-service companies like Google,

and, yes, Facebook.

In the old world, you delivered software in a physical, shrink-wrapped box, on

a yearly release cycle. If you were really aggressive you might ship updates as

often as quarterly, but faster than that and your physical shipping

infrastructure would not be able to keep pace with new versions. As such,

development could proceed in long phases based on those schedules.

In practice what this meant was that in the old world, when development began

on a new version, programmers would go absolutely wild adding incredibly buggy,

experimental code to see what sorts of things might be possible in a new

version, then slowly transition to less coding and more testing, eventually

settling into a testing and bug-fixing mode in the last few months before the

release.

This is where the idea of “alpha” (development testing) and “beta” (user

testing) versions came from. Software in that initial surge of unstable

development was extremely likely to malfunction or even crash. Everyone

understood that. How could it be otherwise? In an alpha test, the engineers

hadn’t even started bug-fixing yet!

In the new world, the idea of a 6-month-long “beta test” was incoherent. If

your software was a website, you shipped it to users every time they hit

“refresh”. The software was running 24/7, on hardware that you controlled. You

could be adding features at every minute of every day. And, now that this was

possible, you needed to be adding those features, or your users would get

bored and leave for your competitors, who would do it.

But this came along with a new attitude towards quality and reliability. If

you needed to ship a feature within 24 hours, you couldn’t write a buggy

version that crashed all the time, see how your carefully-selected group of

users used it, collect crash reports, fix all the bugs, have a feature-freeze

and do nothing but fix bugs for a few months. You needed to be able to ship a

stable version of your software on Monday and then have another stable version

on Tuesday.

To support this novel sort of development workflow, the industry developed new

technologies. I am tempted to tell you about them all. Unit testing, continuous

integration servers, error telemetry, system monitoring dashboards, feature

flags... this is where a lot of my personal expertise lies. I was very much on

the front lines of the “new world” in this conflict, trying to move companies

to shorter and shorter development cycles, and move away from the legacy

worldview of Big Release Day engineering.

Old habits die hard, though. Most engineers at this point were trained in a

world where they had months of continuous quality assurance processes after

writing their first rough draft. Such engineers feel understandably nervous

about being required to ship their probably-buggy code to paying customers

every day. So they would try to slow things down.

Of course, when one is deploying all the time, all other things being equal,

it’s easy to ship a show-stopping bug to customers. Organizations would do

this, and they’d get burned. And when they’d get burned, they would introduce

Processes to slow things down. Some of these would look like:

- Let’s keep a special version of our code set aside for testing, and then

we’ll test that for a few weeks before sending it to users.

- The heads of every department need to sign-off on every deployed version, so

everyone needs to spend a day writing up an explanation of their changes.

- QA should sign off too, so let’s have an extensive sign-off process where

each individual tester does a fills out a sign-off form.

Then there’s my favorite version of this pattern, where management decides that

deploys are inherently dangerous, and everyone should probably just stop doing

them. It typically proceeds in stages:

- Let’s have a deploy freeze, and not deploy on

Fridays; don’t want

to mess up the weekend debugging an outage.

- Actually, let’s extend that freeze for all of December, we don’t want to

mess up the holiday shopping season.

- Actually why not have the freeze extend into the end of November? Don’t want

to mess with Thanksgiving and the Black Friday weekend.

- Some of our customers are in India, and Diwali’s also a big deal. Why not

extend the freeze from the end of October?

- But, come to think of it, we do a fair amount of seasonal sales for

Halloween too. How about no deployments from October 10 onward?

- You know what, sometimes people like to use our shop for Valentine’s day

too. Let’s just never deploy again.

This same anti-pattern can repeat itself with an endlessly proliferating list

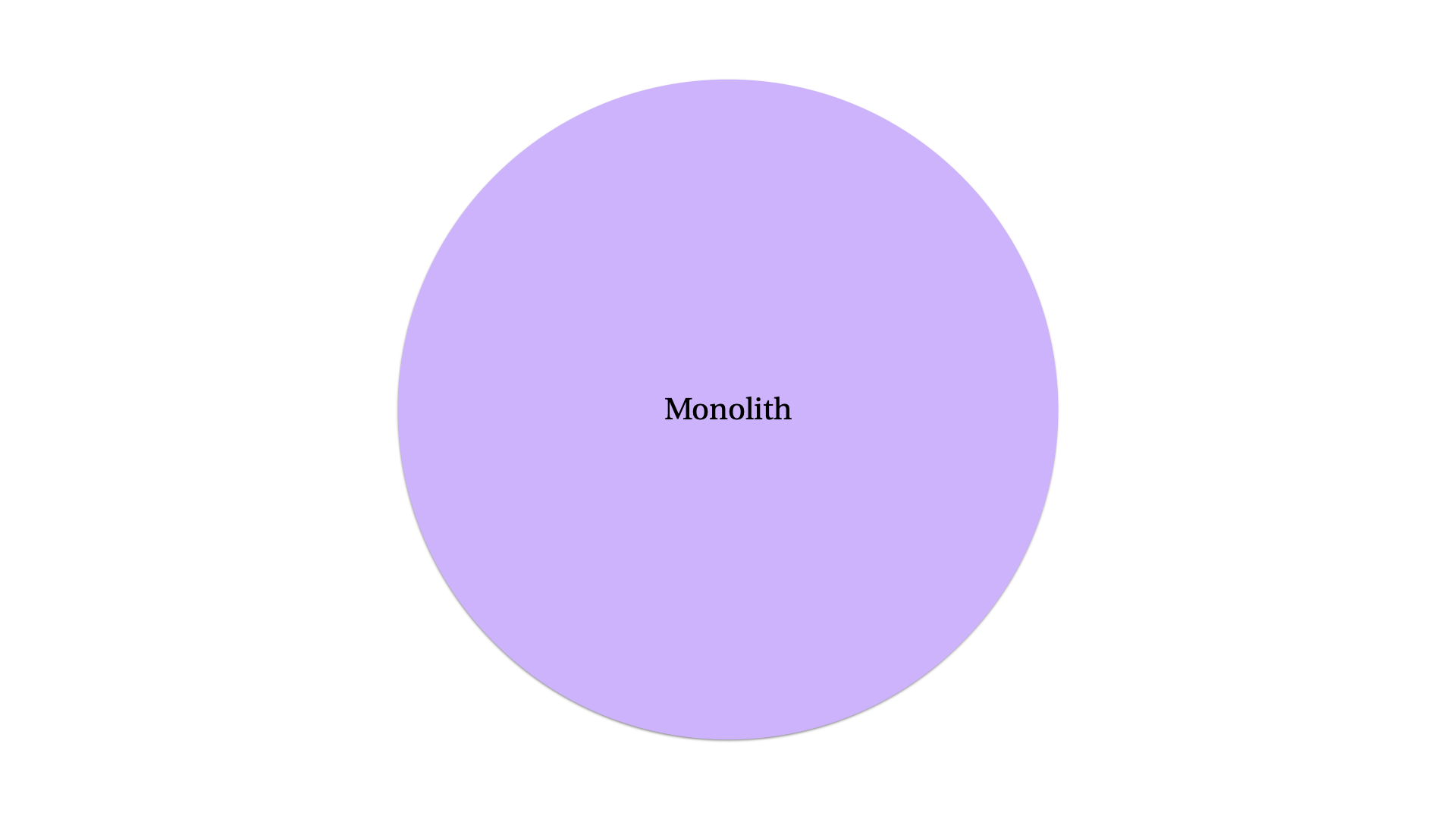

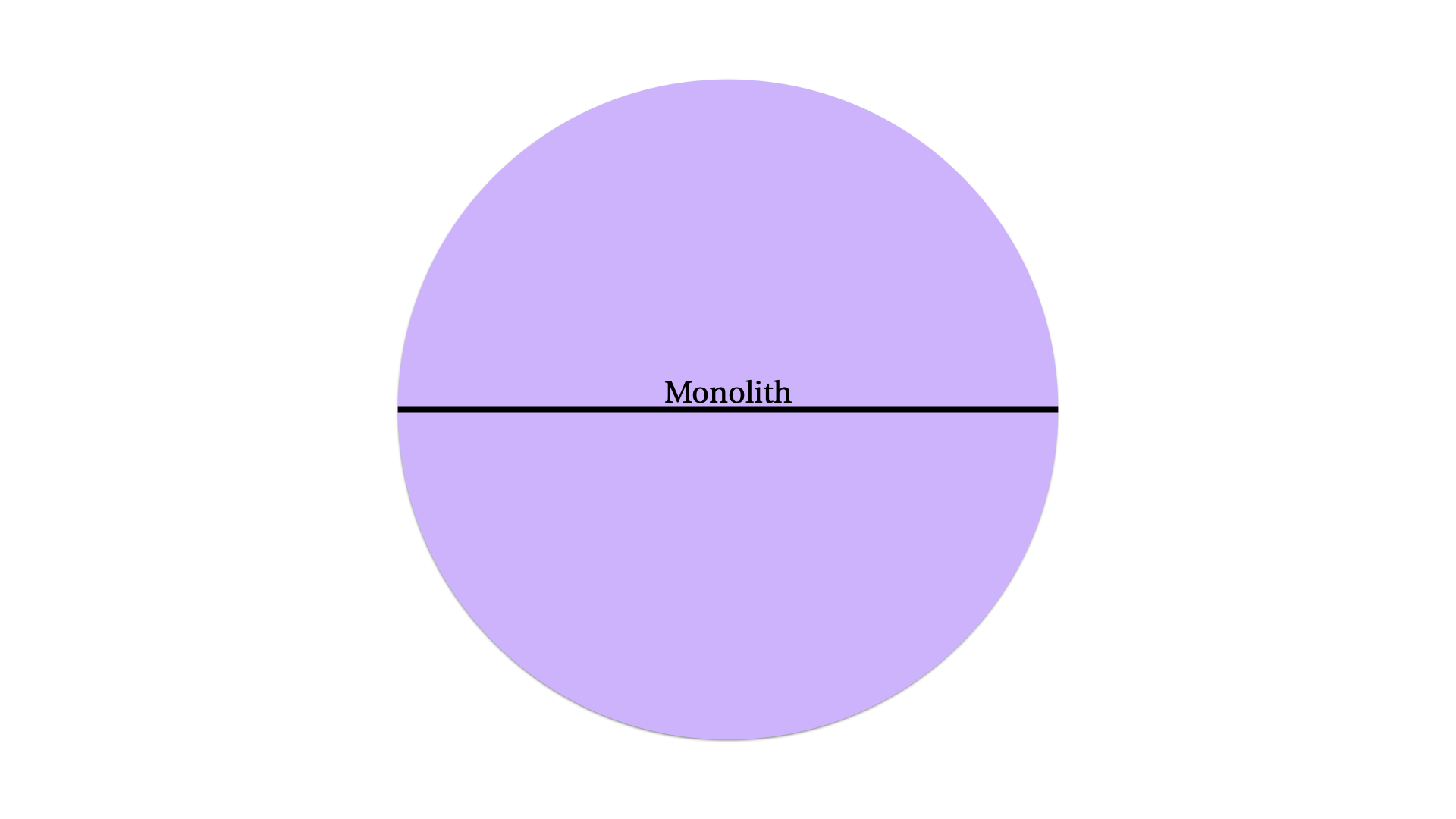

of “environments”,

whose main role ends up being to ensure that no code ever makes it to actual

users.

… and break things anyway

As you may have begun to suspect, there are a few problems with this style of

software development.

Even back in the bad old days of the 90s when you had to ship disks in boxes,

this methodology contained within itself the seeds of its own destruction. As

Joel Spolsky memorably put

it,

Microsoft discovered that this idea that you could introduce a ton of bugs and

then just fix them later came along with some massive disadvantages:

The very first version of Microsoft Word for Windows was considered a “death

march” project. It took forever. It kept slipping. The whole team was working

ridiculous hours, the project was delayed again, and again, and again, and

the stress was incredible. [...] The story goes that one programmer, who had

to write the code to calculate the height of a line of text, simply wrote

“return 12;” and waited for the bug report to come in [...]. The schedule was

merely a checklist of features waiting to be turned into bugs. In the

post-mortem, this was referred to as “infinite defects methodology”.

Which lead them to what is perhaps the most ironclad law of software

engineering:

In general, the longer you wait before fixing a bug, the costlier (in time

and money) it is to fix.

A corollary to this is that the longer you wait to discover a bug, the

costlier it is to fix.

Some bugs can be found by code review. So you should do code review. Some

bugs can be found by automated tests. So you should do automated testing.

Some bugs will be found by monitoring dashboards, so you should have monitoring

dashboards.

So why not move fast?

But here is where Facebook’s old motto comes in to play. All of those

principles above are true, but here are two more things that are true:

- No matter how much code review, automated testing, and monitoring you have

some bugs can only be found by users interacting with your software.

- No bugs can be found merely by slowing down and putting the deploy off

another day.

Once you have made the process of releasing software to users sufficiently

safe that the potential damage of any given deployment can be reliably

limited, it is always best to release your changes to users as quickly as

possible.

More importantly, as an engineer, you will naturally have an inherent fear of

breaking things. If you make no changes, you cannot be blamed for whatever

goes wrong. Particularly if you grew up in the Old World, there is an

ever-present temptation to slow down, to avoid shipping, to hold back your

changes, just in case.

You will want to move slow, to avoid breaking things. Better to do

nothing, to be useless, than to do harm.

For all its faults as an organization, Facebook did, and does, have some

excellent infrastructure to avoid breaking their software systems in response

to features being deployed to production. In that sense, they’d already done

the work to avoid the “harm” of an individual engineer’s changes. If future

work needed to be performed to increase safety, then that work should be done

by the infrastructure team to make things safer, not by every other

engineer slowing down.

The problem is that slowing down is not actually value neutral. To quote

myself here:

If you can’t ship a feature, you can’t fix a bug.

When you slow down just for the sake of slowing down, you create more problems.

The first problem that you create is smashing together far too many changes at

once.

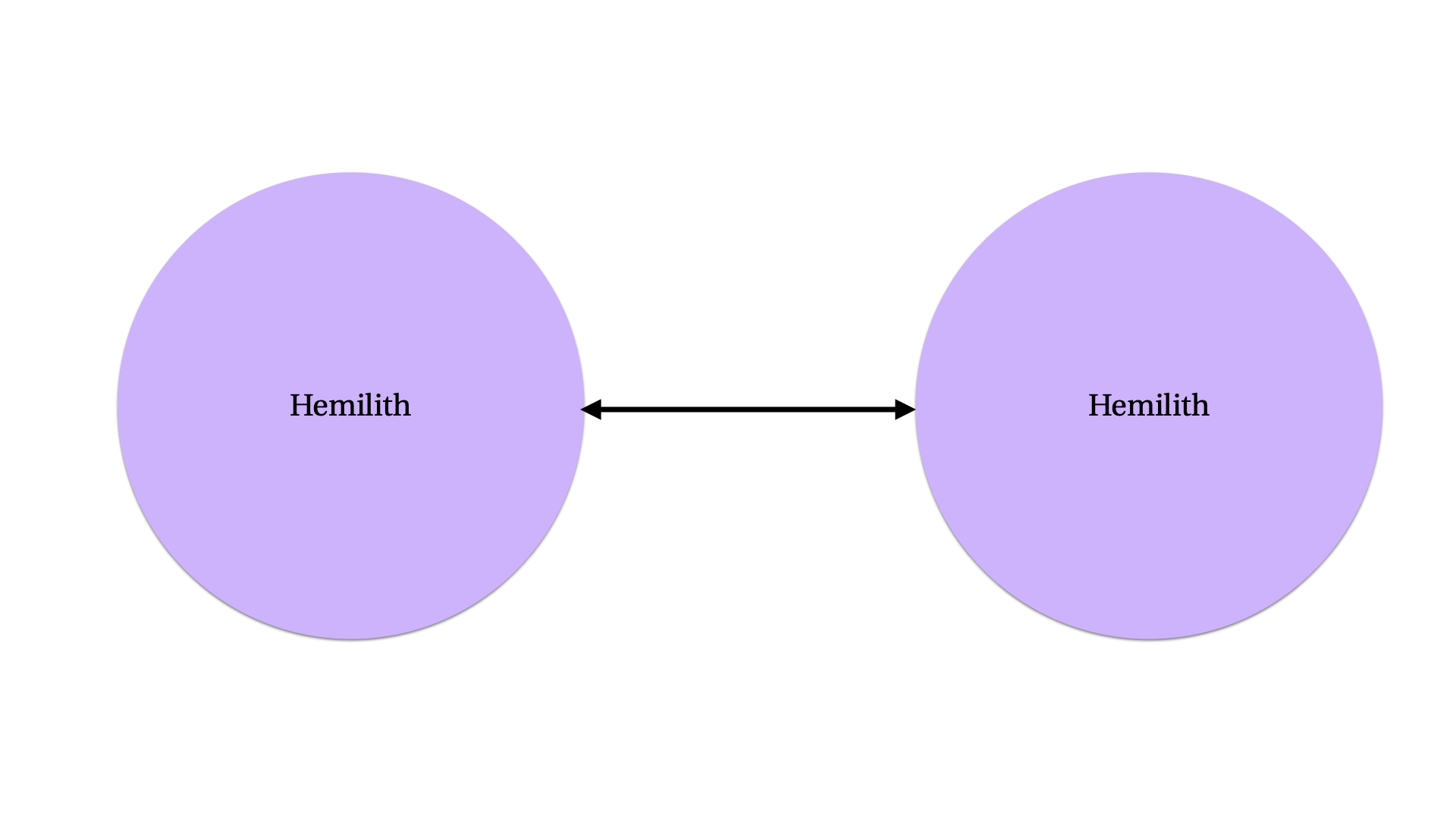

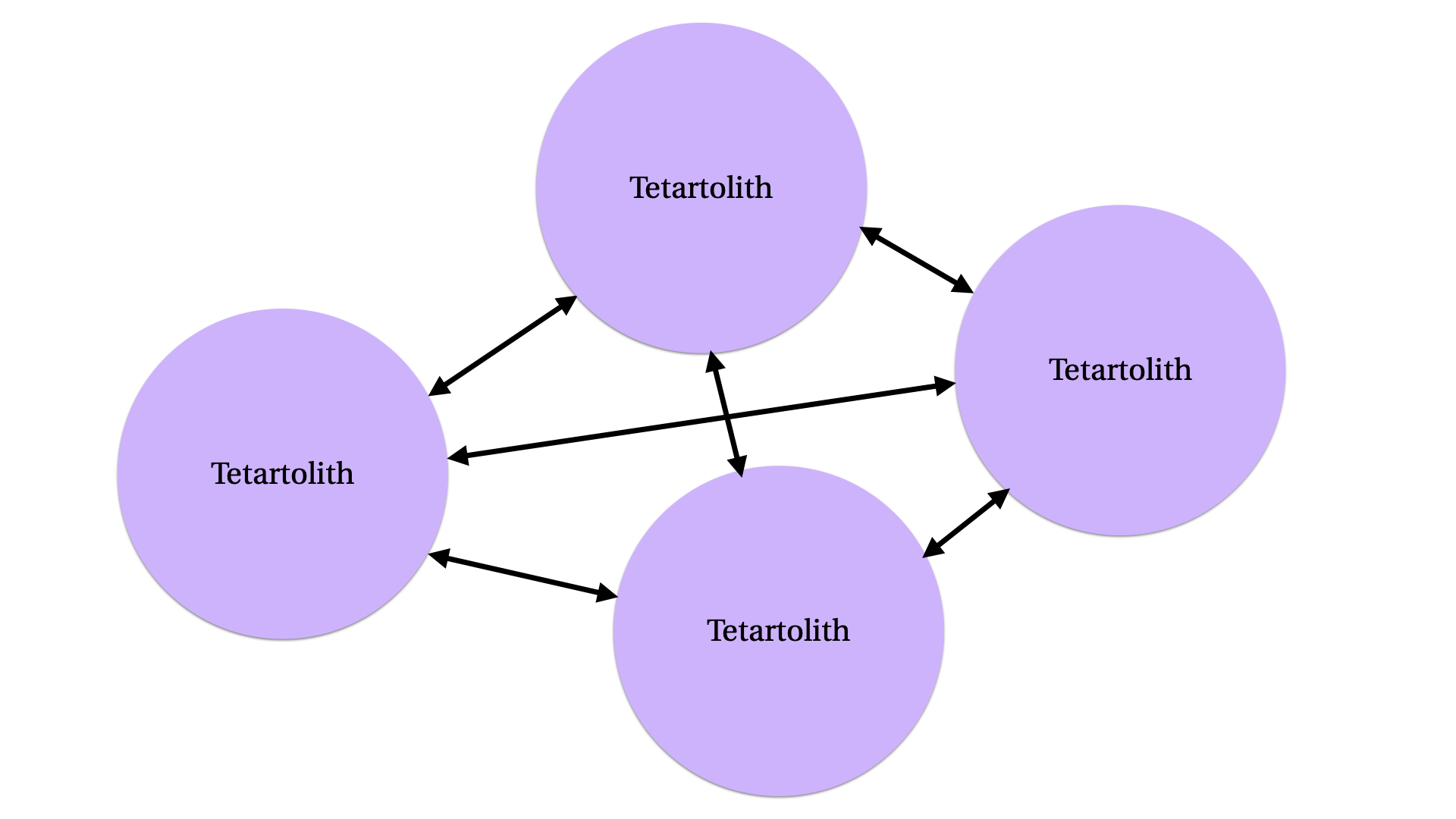

You’ve got a development team. Every engineer on that team is adding features

at some rate. You want them to be doing that work. Necessarily, they’re all

integrating them into the codebase to be deployed whenever the next deployment

happens.

If a problem occurs with one of those changes, and you want to quickly know

which change caused that problem, ideally you want to compare two versions of

the software with the smallest number of changes possible between them.

Ideally, every individual change would be released on its own, so you can see

differences in behavior between versions which contain one change each, not a

gigantic avalanche of changes where any one of hundred different features might

be the culprit.

If you slow down for the sake of slowing down, you also create a process that

cannot respond to failures of the existing code.

I’ve been writing thus far as if a system in a steady state is inherently fine,

and each change carries the possibility of benefit but also the risk of

failure. This is not always true. Changes don’t just occur in your software.

They can happen in the world as well, and your software needs to be able to

respond to them.

Back to that holiday shopping season example from earlier: if your deploy

freeze prevents all deployments during the holiday season to prevent breakages,

what happens when your small but growing e-commerce site encounters a

catastrophic bug that has always been there, but only occurs when you have more

than 10,000 concurrent users. The breakage is coming from new, never before

seen levels of traffic. The breakage is coming from your success, not your

code. You’d better be able to ship a fix for that bug real fast, because

your only other option to a fast turn-around bug-fix is shutting down the site

entirely.

And if you see this failure for the first time on Black Friday, that is not the

moment where you want to suddenly develop a new process for deploying on

Friday. The only way to ensure that shipping that fix is easy is to ensure

that shipping any fix is easy. That it’s a thing your whole team does

quickly, all the time.

The motto “Move Fast And Break Things” caught on with a lot of the rest of

Silicon Valley because we are all familiar with this toxic, paralyzing fear.

After we have the safety mechanisms in place to make changes as safe as they

can be, we just need to push through it, and accept that things might break,

but that’s OK.

Some Important Words are Missing

The motto has an implicit preamble, “Once you have done the work to make

broken things safe enough, then you should move fast and break things”.

When you are in a conflict about whether to “go fast” or “go slow”, the motto

is not supposed to be telling you that the answer is an unqualified “GOTTA GO

FAST”. Rather, it is an exhortation to take a beat and to go through a process

of interrogating your motivation for slowing down. There are three possible

things that a person saying “slow down” could mean about making a change:

- It is broken in a way you already understand. If this is the problem, then

you should not make the change, because you know it’s not ready. If you

already know it’s broken, then the change simply isn’t done. Finish the

work, and ship it to users when it’s finished.

- It is risky in a way that you don’t have a way to defend against. As far

as you know, the change works, but there’s a risk embedded in it that you

don’t have any safety tools to deal with. If this is the issue, then what

you should do is pause working on this change, and build the safety

first.

- It is making you nervous in a way you can’t articulate. If you can’t

describe an known defect as in point 1, and you can’t outline an improved

safety control as in step 2, then this is the time to let go, accept that

you might break something, and move fast.

The implied context for “move fast and break things” is only in that third

condition. If you’ve already built all the infrastructure that you can think

of to build, and you’ve already fixed all the bugs in the change that you need

to fix, any further delay will not serve you, do not have any further delays.

Unfortunately, as you probably already know,

This motto did a lot of good in its appropriate context, at its appropriate

time. It’s still a useful heuristic for engineers, if the appropriate context

is generally understood within the conversation where it is used.

However, it has clearly been taken to mean a lot of significantly more damaging

things.

Purely from an engineering perspective, it has been reasonably successful.

It’s less and less common to see people in the industry pushing back against

tight deployment cycles. It’s also less common to see the basic safety

mechanisms (version control, continuous integration, unit testing) get ignored.

And many ex-Facebook engineers have used this motto very clearly under the

understanding I’ve described here.

Even in the narrow domain of software engineering it is misused. I’ve seen it

used to argue a project didn’t need tests; that a deploy could be forced

through a safety process; that users did not need to be informed of a change

that could potentially impact them personally.

Outside that domain, it’s far worse. It’s generally understood to mean that no

safety mechanisms are required at all, that any change a software company wants

to make is inherently justified because it’s OK to “move fast”. You can see

this interpretation in the way that it has leaked out of Facebook’s engineering

culture and suffused its entire management strategy, blundering through market

after market and issue after issue, making catastrophic mistakes, making a

perfunctory apology and moving on to the next massive harm.

In the decade since it has been retired as Facebook’s official motto, it has

been used to defend some truly horrific abuses within the tech industry. You

only need to visit the orange website to see it still being used this way.

Even at its best, “move fast and break things” is an engineering heuristic,

it is not an ethical principle. Even within the context I’ve described, it’s

only okay to move fast and break things. It is never okay to move fast and

harm people.

So, while I do think that it is broadly misunderstood by the public, it’s still

not a thing I’d ever say again. Instead, I propose this:

Make it safer, don’t make it later.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my patrons who are

supporting my writing on this blog. If you like what you’ve read here and

you’d like to read more of it, or you’d like to support my various open-source

endeavors, you can support my work as a sponsor! I am also available for

consulting work if you think your organization

could benefit from expertise on topics like “how do I make changes to my

codebase, but, like, good ones”.